The "French" Art of the Comeback, Pt. VI: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Florida Man explores the comeback of the final French painter in this series: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

I am continuing my series “The French Art of the Comeback”. I have explored both French political figures and French artists. Here are the links to each of the prior articles:

Bourbons, Talleyrand, Napoleon I: link here

Jacques-Louis David (Part I): painter for Louis XVI

Jacques-Louis David (Part II): painter for Maximilien Robespierre during the French Revolution

Jacques-Louis David (Part III): painter for Napoleon I

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun: link here

Today, I delve into Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a painter who came a bit after both Jacques-Louis David and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. He will be the final French painter whom I discuss in this series. Once I complete this essay, I will return to my broader series “The Art of the Comeback” and move on to Georges Clemenceau, the French prime minister twice: 1) from 1906 to 1909 and 2) from 1917 to 1920.

Early Establishment Approval

David’s Time out of Political Power

Before we dive fully into the comeback of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, we did review a bit about Jacques-Louis David, who trained Ingres. This fact demonstrates the unmatched impact that David had on French art in the late 18th century and early 19th century.

Ingres received his formal artistic education from David in David’s acclaimed studio in Paris. Ingres joined the studio as a pupil in 1797. This period fell in David’s brief time without political influence between the Thermidorian Reaction of 1794 and the Coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799. The Thermidorians during the Thermidorian Reaction guillotined Jacques-Louis David’s Jacobin political ally Maximilien Robespierre, the leader of the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. They did not execute David, but they imprisoned him twice in 1794 and 1795.

Jacques-Louis David regained political power after the Coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799 when Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power as consul, essentially, a dictator of France. David then began serving as a propagandistic painter for Napoleon Bonaparte, who would eventually take the regnal name of Napoleon I when he crowned himself as Emperor of the French in 1804. The Thermidorians ultimately freed David from prison.

Unlike his ally Maximilien Robespierre, Jacques-Louis David did have goodwill with the French citizenry because of his great reputation as a master French painter. After leaving prison in 1795, Jacques-Louis David retreated to private life in Paris. He did not have to exile himself. He did not engage in any political activity. Rather, Jacques-Louis David began teaching young painters in Paris. During this time, he encountered Ingres and taught Ingres in his studio.

Ingres’s Neoclassical Training

David epitomized the French Neoclassical style. Naturally, he trained his students in his Neoclassical style. Ingres was no exception. Even when David abandoned the French monarchy and King Louis XVI in favor of the French Revolution and Robespierre, David never abandoned the Neoclassical style. Sure, the subject matter of his artwork transitioned from Roman legend seen in the 1784 painting The Oath of the Horatii to secular, contemporary revolutionary figures seen in the 1793 The Death of Marat, but both paintings maintained the same stylistic conventions.

After the fall of Maximilien Robespierre and Jacques-Louis David’s return to private Parisian life post-imprisonment, Jacques-Louis David kept painting in the Neoclassical style just as he had done during the French Revolution with The Death of Marat. Nonetheless, he returned to the subject matter of his days painting for French royalty as seen in The Oath of the Horatii. He returned to depicting Roman legend in his 1799 painting The Intervention of the Sabine Women. David made this painting while Ingres was painting — so, naturally, Ingres began painting in the Neoclassical style as well.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Neoclassical training with Jacques-Louis David culminated in Ingres’s 1801 painting Achilles Receiving the Ambassadors of Agamemnon. Ingres was not depicting Roman legend as David was doing. Instead, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was depicting Greek legend, but Greek legend also satisfied the typical subject matter of French Neoclassical art. This painting specifically depicts a scene from Homer’s Iliad, written in the 8th century BC. While the Greeks are struggling in the Trojan War — Achilles, the best Greek warrior, retreated from battle because he had an argument with King Agamemnon, the Mycenaean king of the Greeks. They could not succeed in the war without Achilles, so Agamemnon sends the namesake ambassadors to Achilles to convince him to return to battle.

Beyond the Greco-Roman subject matter, this 1801 painting demonstrates the same Neoclassical conventions that David used and would have taught to Ingres at this time:

drapery

classical Greek nudity

idealized bodies of the men

contrapposto

linear perspective

chiaroscuro

Luckily, for Ingres, the French art establishment still celebrated Neoclassicism, so they gave a large amount of praise to Ingres for this work. Consequently, he earned the Prix de Rome in 1801. The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture awarded the prize, which funded the victor’s artistic studies in Rome for three to five years. The French art school wanted to send their best artists to Rome because they saw classical Greco-Roman art as the paragon of artistic conventions. This love for classical art catapulted Neoclassicism to its height in France. Winning the Prix de Rome demonstrated Ingres’s early establishment approval. In 1774, Jacques-Louis David won the Prix de Rome 27 years before his student Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Unfortunately, for Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, this establishment approval would soon wane.

The Demise of Ingres

Before His Trip to Rome

Even though Ingres won the Prix de Rome in 1801, he actually did not go until 1806 because of political turmoil in France. In the 1790s and 1800s, France was obviously experiencing a large amount of political turmoil. Once Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power, he diverted much of the government’s money to fund the Napoleonic Wars. This delay created an awkward period of time when Ingres was still creating art in Paris before going to Rome.

In a way, this delay blunted his momentum as an artist. Ingres began creating art that earned him derision from the French art establishment. His most controversial piece came with his 1806 painting Napoleon I on His Imperial Throne. The Corp législatif — the legislative body under Napoleon Bonaparte — commissioned this portrait by Jean-August-Dominique Ingres. Why did it foment controversy? With this painting, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was still painting in the French Neoclassical style, which had won him the Prix de Rome just five years prior in 1801. This piece has the drapery, naturalistic bodily proportions, and chiaroscuro emblematic of French Neoclassical painting.

The French art establishment viewed this depiction of Napoleon I as too static and antiquated. Conversely, we can compare Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s depiction of Napoleon Bonaparte to that of Jacques-Louis David, Ingres’s artistic mentor. This image above shows David’s 1801 portrait Napoleon Crossing the Alps. Even though each artist painted his portrait in the Neoclassical style, Jacques-Louis David is incorporating much more movement and emotion in his piece whereas, in Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s piece, he is depicting Napoleon I devoid of any emotion or movement. Napoleon I is just passively sitting in his throne.

Unlike Jacques-Louis David’s piece, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s piece more so resembles medieval Byzantine depictions of rulers from the 6th century AD. The image above displays the Justinian mosaic panel in San Vitale, a Byzantine church in Ravenna, Italy. The mosaic depicts Emperor Justinian of the Byzantine Empire. Soldiers, clergymen, and his royal attendants flank him. The clergyman holding the crucifix is Maximianus, the bishop of Ravenna. The inclusion of all these people communicates that Justinian exudes power in all of these realms in Byzantine society: the state, the military, and the church.

Ingres’s painting and the Justinian panel share a static depiction of each respective ruler. Neither Napoleon I nor Justinian have emotion in their faces. Their depictions have a high degree of frontality. They are looking directly at the viewer. The medieval artists of the Justinian panel were neither sculpting in marble nor painting an elaborate fresco. During antiquity, artist had not honed naturalism in painting yet. That degree of naturalism in painting did not come until the frescoes in the Italian Renaissance and the advent of oil painting in the Northern Renaissance.

Rather, the Byzantine artists who made the Justinian panel used mosaic as the medium. In a mosaic, an artist uses colored glass, hammered gold, and rocks and glues them together with mortar to create an image. The use of colored glass has artistic effects not as easily achieved in paint. Particularly, the colored glass and the hammered gold allow for the reflection of light and subsequent luminescence. The downside of mosaics comes from the fact that they necessarily have lower resolution than that of painting. Therefore, mosaics will almost always have much less naturalism than paintings or sculptures, but the medieval artists did not value the naturalism as much.

You might see that Justinian and everyone else in the mosaic has an elongated quality. In other words, they don’t have natural bodily proportions. We can contrast this fact with a Greco-Roman depiction of a leader, Augustus of Prima Porta. This sculpture depicts Augustus Caeser, the first emperor of Rome. Even though this sculpture has exaggerated musculature in Augustus’s body, his proportions could appear in the natural world. The medieval artists jettisoned these conventions in favor of abstraction and elongation, which gives the visual effect of Justinian floating. This floating implies that Justinian has divine status as if he were an angel floating. The Greeks and Romans valued physical strength and ideal bodily proportions. The medieval artists — in this case, the Byzantines — wanted to emphasize divinity.

The French art establishment thought that Ingres was going too far back in history with his static depiction of Napoleon I. Ironically, Neoclassicism — the premier art form in France at the time — also is going back to a previous time: ancient Greece and Rome. Furthermore, ancient Rome precedes the Byzantine Empire by five centuries! Even though Byzantine art was more recent, the Enlightenment thinkers in Europe at the time saw the medieval era as “dark” and “unenlightened”, hence the pejorative term the “Dark Age”. I always have seen that term as a cheap way for deists and atheists of the Enlightenment to diminish the beautiful art of the medieval age. You cannot discount medieval art. Look at the magnificent French Gothic cathedrals, but I suppose that — during the French Revolution — the Jacobins defaced them to create Temples of Reason in the process of de-Christianization in France.

Even if David was returning to an older style, the Neoclassical painters were adding modern elements to these paintings. In Jacques-Louis David’s portrait, Napoleon Bonaparte is wearing modern military gear. David is depicting a contemporary figure. Even though David is mythologizing what Napoleon did when he crossed the Alps from France into Italy. With the Enlightenment, the French people were taking old ideas but adapting them to the modern age while Ingres was just reverting without any outlook toward the future.

Ingres’s Time in Rome

Five years after winning the Prix de Rome, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres did eventually make to Rome. Unfortunately, for him, during that intermediate period of five years in France, he had lost his luster because of derided pieces like Napoleon I on His Imperial Throne. Nevertheless, the French government still had an obligation to fund Ingres’s stay in Rome since he won the Prix de Rome.

Whenever the French government awarded the Prix de Rome and sent an artist to Rome, the artist would have to send “envoi paintings” back to France to prove that he was developing his artistic talents in Rome. The Académie des Beaux-Arts specifically organized the stay in Rome. Put simply, the artist needed to prove that the French government would be getting a return on its investment. After his stay in Rome, France would be getting an even more masterful artist.

Unlike his mentor Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was not impressing the Academy with his envoi paintings from Rome. Ingres was receiving the same sort of derision for his envoi paintings as he did with Napoleon I on His Imperial Throne. He received the exact same critiques that he was painting too statically with too little emotion or drama.

Jupiter and Thetis (1811)

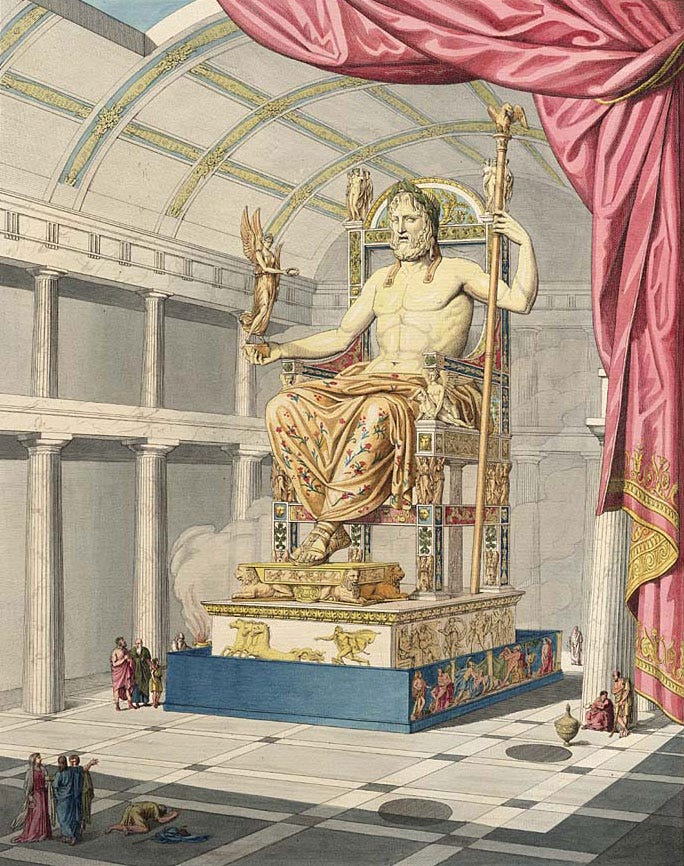

The image above shows one of Ingres’s envoi paintings during his time in Rome — 1811’s Jupiter and Thetis. Ingres had chosen a subject related to the painting that had earned him the Prix de Rome in 1801 — Achilles Receiving the Ambassadors of Agamemnon. The latter depicts mortal humans amid the Trojan War in a scene in Homer’s Iliad. The later painting Jupiter and Thetis depicts another scene from the Iliad, but — this time — Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres is painting gods. I will note that the Iliad is Greek, but — when the French painted Greek mythological scenes — they referred to the figures with their Roman names. Consequently, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres uses the name “Jupiter” instead of “Zeus”.

In the painting, the sea nymph Thetis — the mother of Achilles — is begging Zeus to intervene in the Trojan War. Thetis specifically wants to punish Agamemnon and Greeks because Agamemnon had insulted Achilles. She wants him to do so by tilting the scales for the Trojans to show Agamemnon and the Greeks that they need Achilles.

Just as he did with Napoleon I, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres depicts Jupiter sitting on a throne with great frontality. He is looking directly at the viewer. He has zero emotion while Thetis is pleading to him. Both Napoleon I and Jupiter dominate their respective canvases, but Ingres was not basing this painting specifically on Napoleon I on His Imperial Throne. Ingres was basing the depiction of Jupiter on one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: the Statue of Zeus at Olympia. The image above displays a rendition of it in the sanctuary of Olympia. Phidias, the same person who sculpted the Elgin Marbles in the Parthenon, sculpted the Statue of Zeus. Just as Jupiter does in Ingres’s painting, Zeus is sitting statically on a huge throne. He also has one arm up with his hand holding his scepter.

You would think that the Academy would appreciate this painting by Ingres. After all, it is harkening back to the styles of ancient Greece and Rome, but — as I already wrote — good French Neoclassicism adapted the past for contemporary times. David added emotion, and — even when he was depicting Roman legend — those depictions served as allegories of what was happening in France at the time. His 1784 painting The Oath of the Horatii tried to call people to pledge loyalty to King Louis XVI and the French monarchy. His 1799 painting The Intervention of the Sabine Women alluded to the fact that David might have been trying to atone for what he did during the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror.

Ingres usually depicted Greek and Roman legend, but one of his other envoi paintings made in Rome delved into scandalous territory. Sure, the Academy did not like Jupiter and Thetis, but Ingres was still painting subjects fit for French Neoclassicism. In 1808, while he was still studying in Rome, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted La Grande Baigneuse and sent it back to France. This painting would prefigure his most famous painting: 1814’s La Grande Odalisque.

La Grande Baigneuse (1808)

The image above shows Ingres’s 1808 envoi painting La Grande Baigneuse, which translates in English to The Great Bather. Unlike his other paintings at this time, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres is not depicting any narrative. He is painting neither Greco-Roman legend nor a contemporary leader like Napoleon I, both appropriate subjects in French Neoclassicism even if the French art establishment did not like Ingres’s portrait of Napoleon I. In La Grande Baigneuse, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres is simply depicting a nude woman who is either coming back from a bath or preparing to get into the bath.

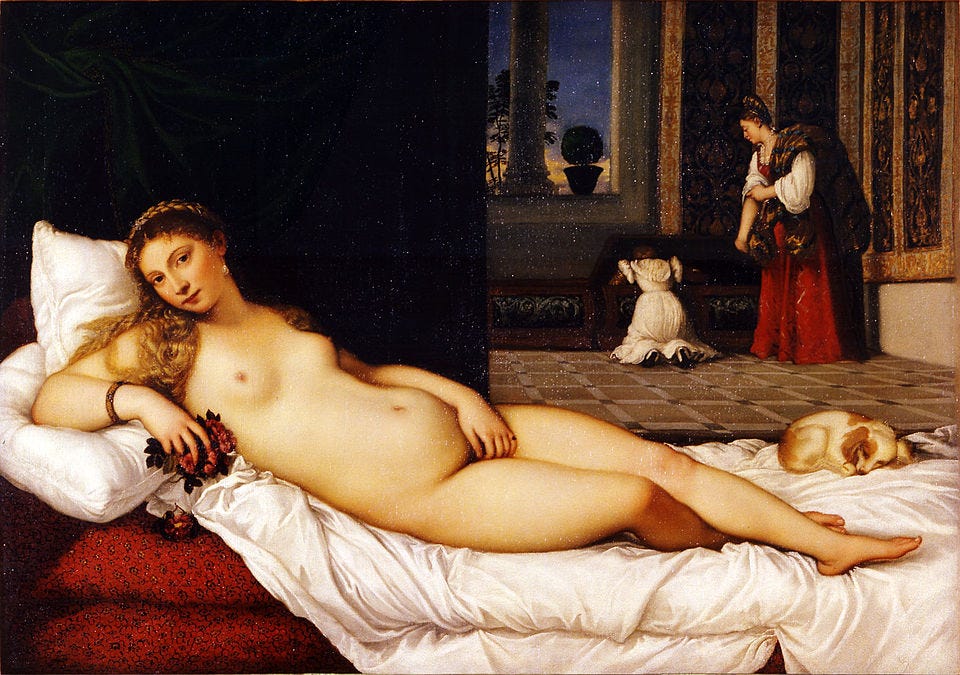

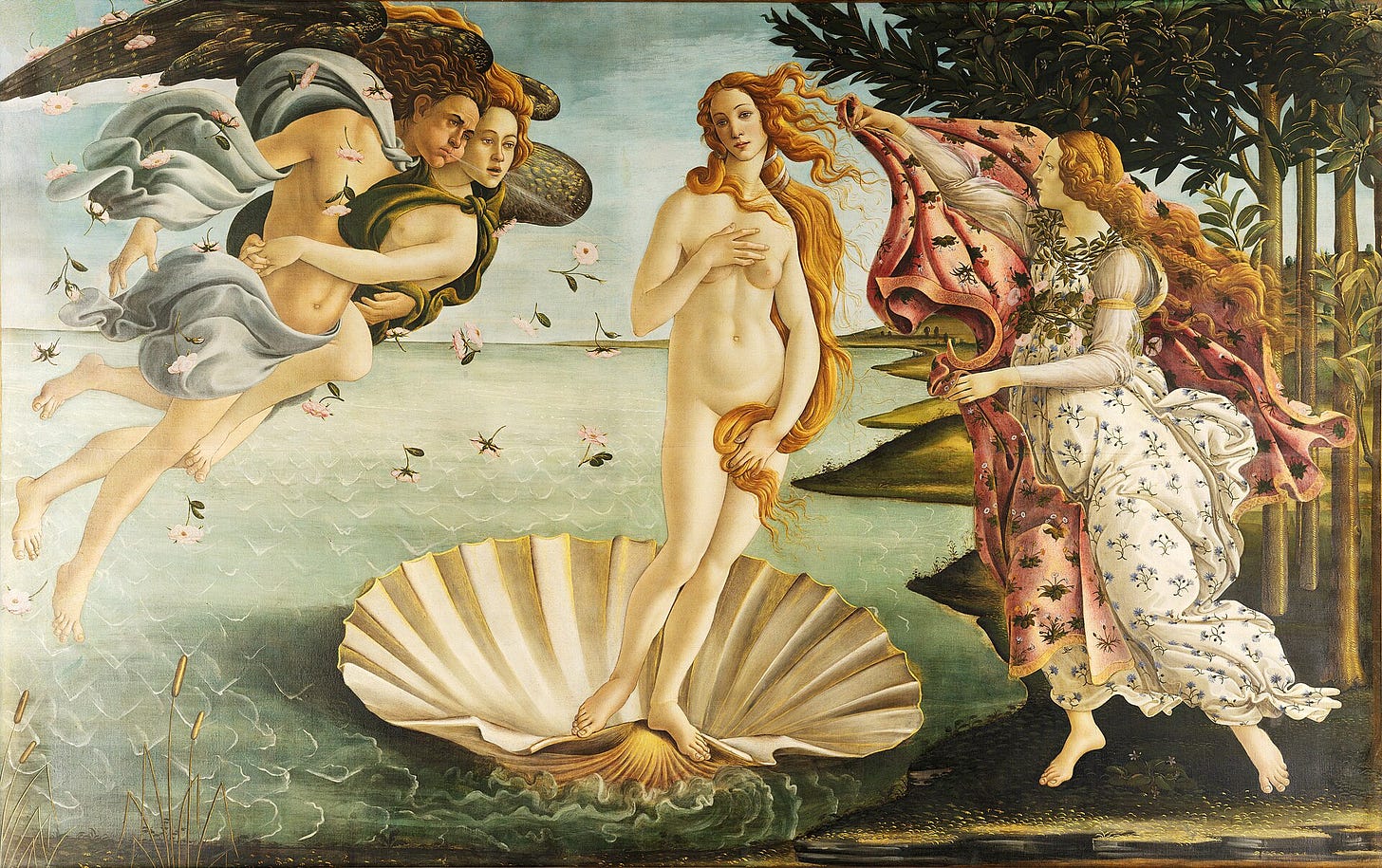

The nudity on its own did not elicit scandal. Renaissance artists and Greco-Roman sculptures, whom the Neoclassical artists wanted to emulate, had depicted women in the nude. The images above show examples from both ancient Greece and the Italian Renaissance. The image on the top shows the Hellenistic Greek sculpture Venus de Milo, one of the most universally recognizable Greek sculptures. The image on the bottom shows Titian’s 1534 painting Venus of Urbino. Titian’s painting popularized the genre of reclining nude. Titian’s piece came in the Italian Renaissance, 17 centuries after the creation of Venus de Milo.

Due to their nudity, one could view both of theses pieces as sensual. Wouldn’t that be scandalous? The sculpture Venus de Milo is much less explicit than Venus of Urbino is. The former is not looking at the viewer even though she is nude. On the other hand, Venus of Urbino depicts a woman nude on a bed as she looks at the viewer. We can see all of her bottom except for her genitalia. The inclusion of a bed has sexual implications. She has luminous blonde hair and pale skin, both idealized features in a woman at this time.

On their own, without any additional context, one could view either of these pieces as erotic, especially, Venus of Urbino — but these pieces escape any scandal because of which woman they both depict. Both pieces depict Venus — the Roman goddess of love, beauty, desire, sex, and fertility. The Greeks referred to her as Aphrodite. As I already wrote, when we refer to depictions of Greco-Roman gods and goddesses in art, we use the Roman names.

If an artist is depicting a deity in either painting or sculpture, then he is going to emphasize the deity’s domain. Artists depict Jupiter as having an ideal, muscular body to communicate masculine strength. As for Venus, artists will depict her as physically attractive since she is the Roman goddess of beauty and sex.

I think that people were unfairly and hypocritically deriding Ingres’s La Grande Baigneuse when we consider the admiration of Venus De Milo and Titian’s masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance. In addition to Venus of Urbino, we can consider Sandro Botticelli’s tempera painting The Birth of Venus, circa 1484-1486. I show this painting in the image above. This one is much less sensual than Venus of Urbino is. In Sandro Botticelli’s painting, even though Venus is still nude, she is covering up more of her body. She is not laying on a bed, and she is not looking at the viewer.

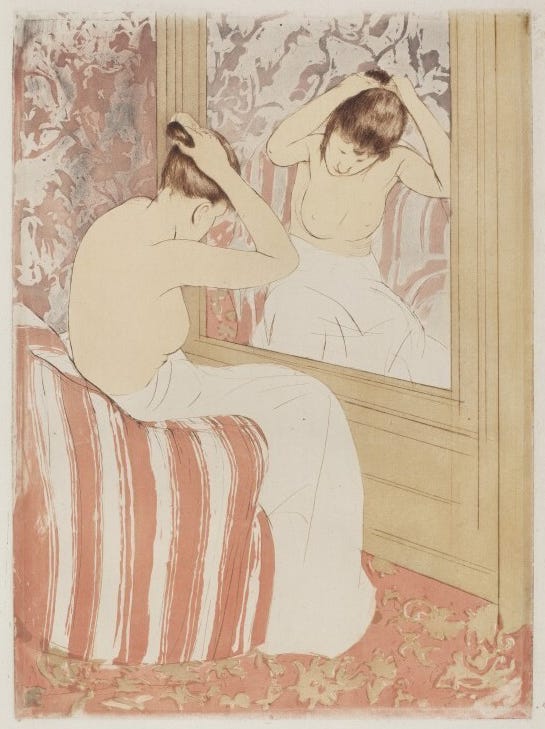

How is La Grande Baigneuse any more erotic or more scandalous than Venus of Urbino? Even though the woman in Ingres’s painting is nude, you cannot see much of her body. You cannot see her face. You cannot see her breasts. She is not looking at you. She is still lying on a bed, but she is not doing so in a sexual context. As the title suggests, she has just completed the routine task of bathing, something that we all do every day. Ingres’s painting very much resembles, in subject matter, a painting that would come later eight decades later — Mary Cassatt’s piece The Coiffure — created between 1890 and 1891. I display this piece above.

The woman in The Coiffure is similarly doing an everyday, routine task on her bed even if Cassatt depicted the woman as nude just as Ingres did. The woman whom Casssatt painted is preparing her hair in the morning. Pretty much every woman does so in the morning as well. Just as I argued about La Grande Baigneuse, I do not view The Coiffure as very erotic even though the subject is nude while I see Venus of Urbino as erotic.

The woman in Venus of Urbino is looking directly at you as if she is inviting you to the bed, yet the Academy viewed Venus of Urbino as acceptable because it was depicting the goddess Venus, a very common subject in art from both the antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. I posit that painters in the Renaissance and sculptors in antiquity painted Venus in the nude as an excuse to just depict a nude woman in an art work. These artists were virtually all men. This fact is where we get the idea of the “male gaze” in art. Male artists historically have depicted women in objectified manners. Nevertheless, La Grande Baigneuse served as an entry point for Ingres to paint even more erotic pieces later, particularly, his 1814 painting La Grande Odalisque.

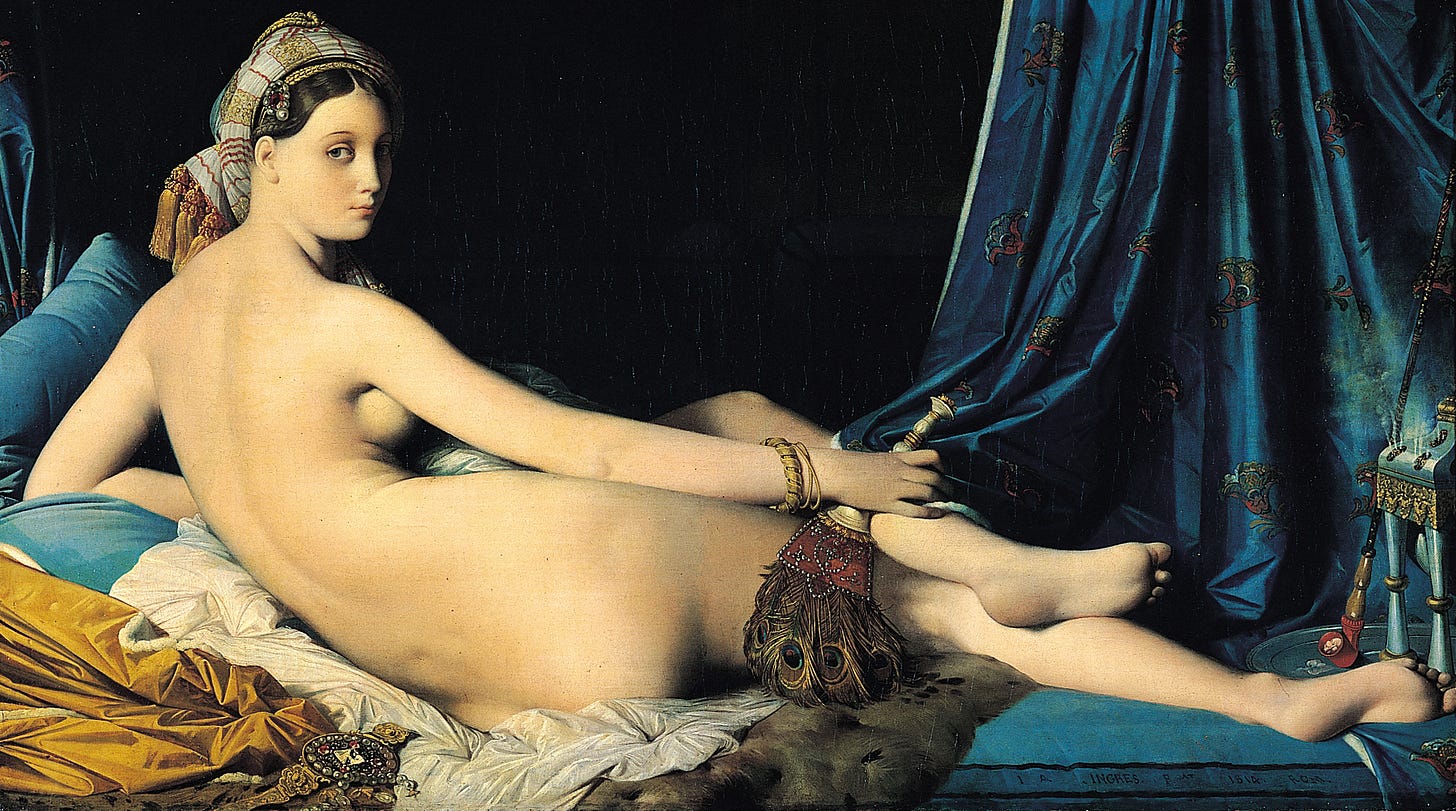

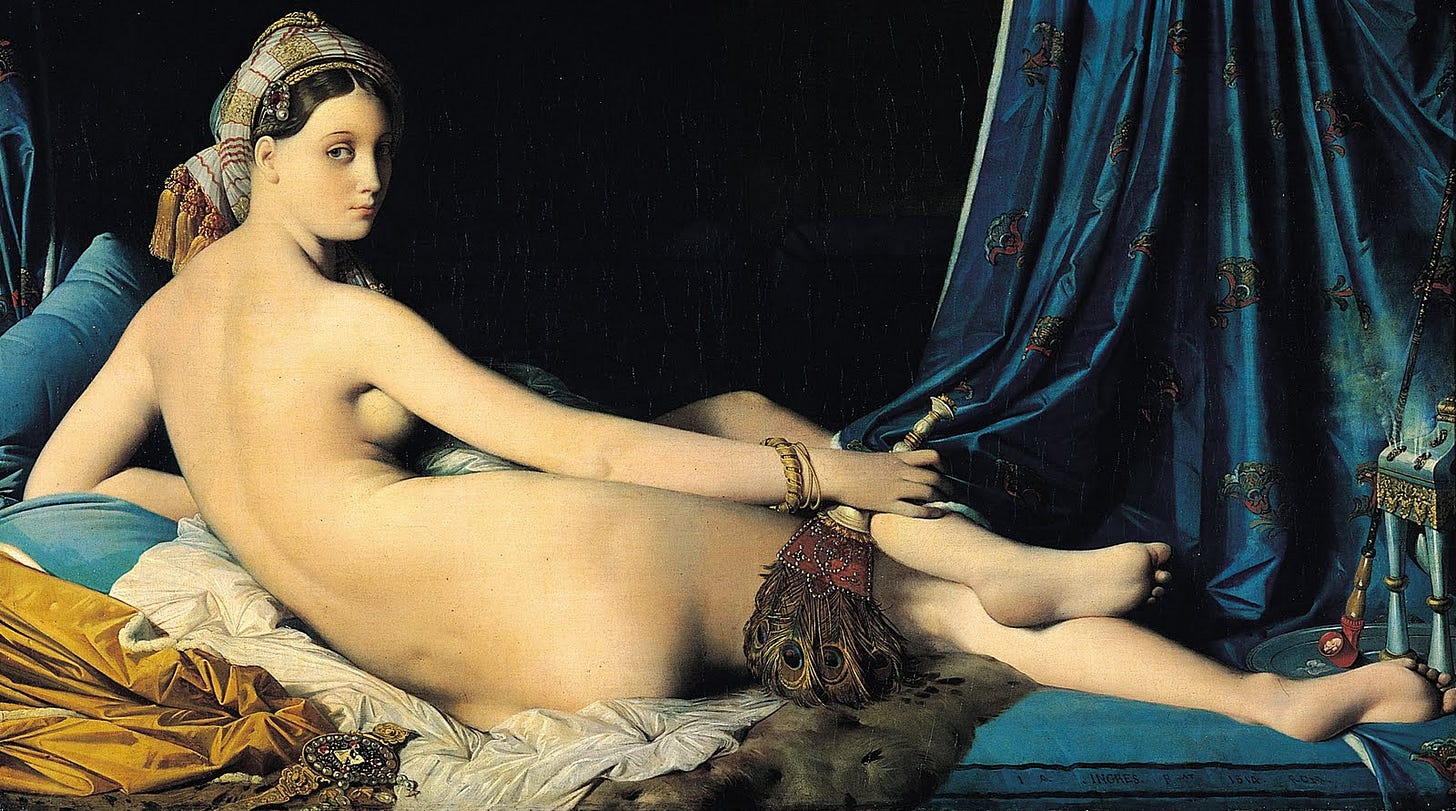

Transition to Romanticism: La Grande Odalisque (1814)

By 1810, Jean-Auguste-Dominique-Ingres had completed his training and envoi paintings for his trip for the Prix de Rome although he continued to live in Italy. Ingres would not return to France until 1824, eighteen years after the beginning of his trip for the Prix de Rome. He spent much more time in Italy than the vast majority of winners of the Prix de Rome would. He avoided returning to France because of the criticism that he was receiving from the French art establishment.

In 1814, while he was still working in Rome, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted one of his most famous works: La Grande Odalisque. Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister Caroline commissioned the painting. At the time, she was the queen of Naples by virtue of her marriage to Joachim Murat, the king of Naples. Murat was a Frenchman who served as a military officer during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon I installed him as the king of Naples as Napoleon I was broadening his power and influence throughout many different states in Europe. Napoleon I famously installed many of his family members as the monarchs of many different European states.

Joseph (older brother) — King of Spain (1808-1813)

Louis (younger brother) — King of Holland (1806-1810)

Jerome (younger brother) — King of Westphalia1 (1807-1813)

Strangely, the art establishment back in France was not accepting Ingres’s work, but the sister of the French Emperor Napoleon I was commissioning Ingres’s paintings.

Ingres’s 1814 painting La Grande Odalisque (shown at the beginning of this section) depicts another nude woman. More so than La Grande Baigneuse, the 1814 painting La Grande Odalisque resembles Titian’s 1534 painting Venus of Urbino. One could argue that Ingres was making a direct reference because of the use of the convention of the reclining nude. Just as the woman in Venus of Urbino was doing, the woman in La Grande Odalisque is lying on a bed and looking at the viewer.

Unlike what he did with La Grande Baigneuse, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres gives additional sensual context to La Grande Odalisque. In English, the term “odalisque” translate to “harem slave” or “concubine”. She is a concubine in a harem, assumedly, somewhere in the Ottoman Empire based on the styles in the painting. She is holding an oriental brush. The curtains have oriental designs, and — beside her feet — there is a hookah, a device used to smoke tobacco in the Middle East.

These aspects of the painting reflect the trend of Orientalism in European art at the time. European artists had a strangely strong interest in subjects in the Orient, but they did so in a way that made the culture into something alien and exotic. With La Grande Odalisque, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres is sexualizing and objectifying a Turk woman. She has no name. Ingres just refers to her as the “concubine” if we translate the title to English.

The French art establishment further derided Ingres for La Grande Odalisque. He had depicted something gratuitous and grotesque. Not only had he painted a nude woman not named Venus, but he had also painted a sex slave. Ingres could obfuscate the profanity of La Grande Baigneuse, but the sexuality was apparent in La Grande Odalisque.

The scandal did not stop with the subject of the painting. The French salons critiqued the painting for its inaccurate depiction of the human body. Ingres had given the concubine a distorted and elongated back. Neoclassicism emphasized the ideal, naturalistic proportions of the human body as seen in Greco-Roman sculpture and Italian Renaissance painting. With La Grande Odalisque, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres does harken back to an artistic style in Italy peripheral to the Renaissance. His depiction of the concubine matches that of Mannerism.

In the image above, I show Parmigianino’s 16th-century painting Madonna with the Long Neck, perhaps the most iconic example of Italian Mannerism. Parmigianino depicts the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child. The Italian word “Madonna” translates into English as “my lady” but mostly commonly refers to Virgin Mary. Unlike the Italian Renaissance paintings, Parmigianino’s painting gives both Virgin Mary and the Christ Child very unrealistic, elongated proportions, hence the name “Madonna with the Long Neck”. The Christ Child almost looks alien, and Mary appears to have additional vertebrae in her neck.

Ingres similarly adds these alien body proportions to the concubine in La Grande Odalisque. Just as Mannerism departed from the Italian Renaissance, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was departing from Neoclassicism and steering toward Romanticism. Ingres was not fully embracing this style yet, but La Grande Odalisque demonstrates a few aspects of Romanticism.

less strict adherence to anatomical proportions

high emotional intensity

an interest in the Orient

The image above shows Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 painting Liberty Leading the People, a great example of how French Romanticism would evolve. This painting depicts a mythologized version of the July Rebellion in France in 1830. This rebellion overthrew the Bourbon monarchy for the final time, which the French Revolution did not fully achieve four decades earlier. You can see that this painting depicts a mythological because of the inclusion of the French personification of Liberty holding the tricolor French flag. You can see her bare chest. No bare-chested woman would be leading a rebellion.

Beyond the nudity, this painting has no clear ground line. Dead bodies lie on top of each other in a non-naturalistic manner. This piece includes the emotionality, both positive and negative, of Romantic art. The positive emotion comes from the prospect of liberty for the French people and overcoming the monarchy, but we can see negative emotion in the fact that so many Frenchmen had to die in the process of liberating France. This painting shows the cost of war and revolution.

Ingres’s Comeback

The Tenuous Legitimacy of the Restored Bourbon Monarchy

After the derision of La Grande Odalisque in 1814, Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres voluntarily exiled himself to Rome, where he produced those negatively received envoi paintings during this studies for the Prix de Rome. He spent 10 years in Rome. He still painted, but he would get another chance in the French art establishment, in 1815, after the fall of Napoleon I and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. Ingres eventually painted The Vow of Louis XIII, shown above, at the 1824 Paris Salon.

The Académie des Beaux-Arts would host the Paris Salon every two years to exhibit the best art in France of the prior two years. The change in politics in France allowed for Ingres to execute a comeback. He could take advantage of the establishment’s desire to return to glorifying the Bourbon monarchy. With The Vow of Louis XIII, Jean-August-Dominique appealed to those monarchist sentiments. He depicts King Louis XIII, who reigned from 1610 to 1643, so his monarchy came around two centuries before Ingres painted The Vow of Louis XIII.

Louis XIII was the great-great-great-grandfather of Kings Louis XVI, Louis XVIII, and Charles X. When Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres exhibited The Vow of Louis XIII, Charles X had just started his reign the death of his older brother Louis XVIII. France had just had such a chaotic past four decades with the execution of Louis XVI, the two rises of Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Bourbon Restoration. The French could not decide which form of government they wanted. After Napoleon I’s failed invasion of Russia, he left power in April 1814 and went into exile in Elba. Louis XVIII, of the Bourbon family, returned to power — but he only returned for 10 months. Louis XVIII finally returned in a long-term capacity in July 1815 after Napoleon I’s failure at Waterloo, subsequent final fall from power, and exile to St. Helena.

Even though the Bourbons regained control of France in 1815, they never could re-achieve the long-term legitimacy and acceptance from the French citizenry that they had before the French Revolution. No longer would we see extremely long reigns seen with Louis XIV and his great-grandson Louis XV — who, respectively, reigned for 72 years and 69 years. Consequently, the Bourbon monarchy needed new propagandistic art in an attempt to establish their authority. The Bourbon monarchs before the French Revolution benefited from propaganda as did Napoleon I. Surely, this strategy could work again for the newly crowned Charles X, who had the additional goal of becoming more absolutist than his brother and direct predecessor Louis XVIII. Charles X wanted to more so emulate his great-grandfather Louis XIV. Out of any other monarch in European history, Louis XIV serves as the greatest embodiment of absolute monarchy.

The Vow of Louis XIII (1824)

With The Vow of Louis XIII, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Inges attempt to appeal to the French citizenry’s nostalgia for the old Bourbon monarchs. He paints Louis XIII, a very beloved Bourbon monarchy. Nobody had depicted a Bourbon monarch at such a prevalent and laudatory level in many years since the years before the French Revolution. Ingres also communicates the concept of divine right for the Bourbons in France. The painting depicts King Louis XIII kneeling before the Virgin Mary, who is holding the Christ Child. Ingres also includes two putti to the right of Louis XIII. Putti are artistic depictions of winged, nude baby angels — very prominent in Renaissance and Baroque art. They originate from the ancient Greco-Roman artistic convention of the Erotes — also winged, nude babies who accompanied Aphrodite in Greek paganism and Venus in Roman paganism.

The painting depicts a real historic event although Louis XIII never physically kneeled before the Virgin Mary or the Christ Child. In 1638, King Louis XIII officially dedicated himself, the French state, and the future monarchy to the Virgin Mary. This literal depiction of Christian icons departs from the art of the previous four decades. It refers to a very religious and historical era that precedes the de-Christianization of France during the Revolution. Even though Napoleon Bonaparte re-established Catholicism as the state religion of France, propagandistic artwork of him virtually would never literally depict Christian icons as we see in The Vow of Louis XIII with the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child.

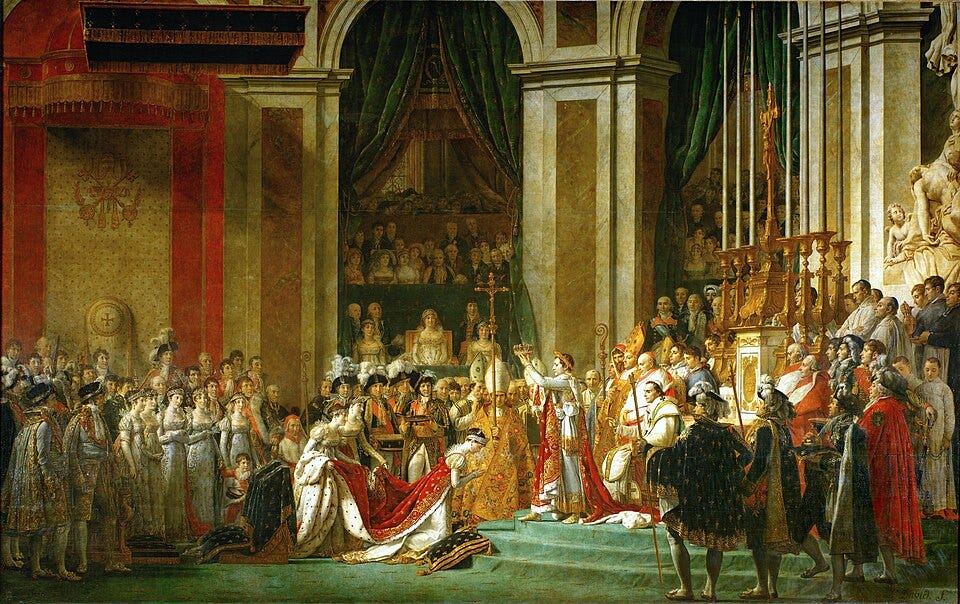

The artwork during Napoleon Bonaparte’s time in power only allegorically referred to Christianity. David painted the most famous religious piece during the Napoleonic era with his 1807 painting The Coronation of Napoleon, shown in the image above. Although this painting idolizes Napoleon Bonaparte, it is depicting a realistic event in Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris when Napoleon Bonaparte coronated himself as the Emperor of the French and took the regnal name of Napoleon I. David was making two messages about Christianity with this painting.

Firstly, France was ending its period of de-Christianization during the French Revolution. In 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte re-established Notre Dame as a Catholic cathedral as opposed to an atheistic Temple of Reason, its status during the French Revolution. He had done so as a part of his Concordat of 1801 when Napoleon Bonaparte re-established a relationship with the Catholic Church and Pope Pius VII and Catholicism as the state religion of France.

Secondly, Jacques-Louis David was again insinuating that Napoleon I had divine right, but David did not depict Christ at all in this painting. Sure, we can see the crucifix with Christ over the altar in Notre Dame, but this is still a realistic depiction of how the coronation ceremony would have looked. David is not painting an unrealistic depiction of Napoleon I with Jesus. If Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres had painted this depiction of Napoleon I in the Romantic era, then Ingres could have very possibly painted Napoleon I physically with Jesus or Virgin Many as he did with Louis XIII in The Vow of Louis XIII.

Because of the royalist and pro-Christian sentiments of the French establishment in the 1820s, they applauded Ingres’s painting The Vow of Louis XIII at the 1824 Salon. No longer was Ingres painting nude, sexualized concubines in the Ottoman Empire. He was painting a virtuous French king dedicating himself and France to the Virgin Mary. Ingres was exemplifying virtue just as David did with The Oath of Horatii except that Ingres was including many more overt Christian themes in his work. Much of the French Neoclassical art eschewed overt Christian imagery for Greco-Roman imagery, Ancient Greece obviously predated Christianity. Most of the history of ancient Rome predated Christianity, and — after Christianity became popular — the Roman Empire persecuted Christians until Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313 AD.

After The Vow of Louis XIII, Jean-Auguste-Dominique continued his ascent back into the French art establishment. In 1834, King Louis-Philippe I — the French king after the July Revolution in 1830 — appointed Ingres as the director of the French Art Academy in Rome. Ingres served in that position until 1841. He helped the young French painters who had won the Prix de Rome. By that point, he was 61 years old and returned to private studio life although he would make one more comeback as an older man.

Ingres’s Controversy in His 70s

In his old age, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was coasting off the fact that he had regained establishment approval in the 1820s. When he retired from his position as director of the French Art Academy in Rome, he returned to painting in a private studio. Ingres clearly executed his comeback by shifting from erotic subjects seen in the 1814 painting La Grande Odalisque to pro-monarchy subjects seen in the the 1824 painting The Vow of Louis XIII. One might expect a painter to moderate even more in his old age and try to elicit less controversy. Artists often make their controversial works in their early careers.

Instead of living a quiet, non-controversial life in his old age — Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres returned to the themes seen in La Grande Odalisque. In 1862 at the age of 82, he completed the painting The Turkish Bath, which I show in the image above. This painting increases the eroticism seen in La Grande Odalisque, painted 48 years earlier. He is again returning to the subject of harem slaves in the Near East, hence the title “The Turkish Bath”. Not only is he returning to nudity, but he is also adding dozens of naked women! He is including similar imagery to that of La Grande Odalisque. The central woman with her back turned toward the viewer is wearing a turban, indicative of the Turkish culture.

Ingres is revealing much more of the women’s bodies than he did with the singular woman in La Grande Odalisque. We can also see the entirety of many of the women’s breasts in The Turkish Bath whereas, in La Grande Odalisque, we cannot see the entirety of the women’s breasts despite the fact that it was controversial for its erotic nature at the time. As I have already written, when Renaissance painters or antiquity sculptors would depict nude women, they often were depicting Venus or Aphrodite, the goddesses of beauty. Those artists idealized Venus with blonde hair and slender proportions. On the other hand, in The Turkish Bath, many of the women have higher body fat. They are not conventionally attractive in the way that artists in the Italian Renaissance or antiquity would depict idealized women.

Lasting Influence of Ingres

The French art establishment did not approve of The Turkish Bath as they did with The Vow of Louis XIII. Very clearly, the salons critique it for its erotic and gratuitous nature. They criticized it in the same manner that they criticized La Grande Odalisque almost half a century earlier, but Ingres did not have much more career after he completed The Turkish Bath. He died five years later, but The Turkish Bath would live on in its influence on modern painting in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

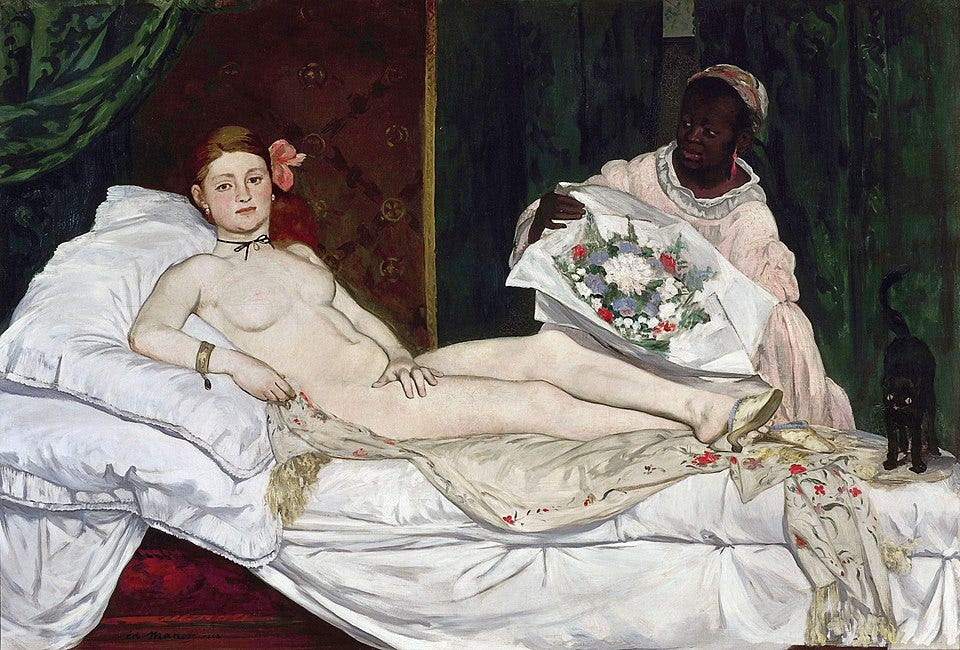

French Realism in 19th Century

We can see the first major influence from Ingres in the French Realist paintings of artists like Édouard Manet or Gustave Courbet. The image above shows Manet’s 1863 painting Olympia, perhaps the most iconic painting of the French Realist style. Manet is referencing the genre of the reclining nude seen in both Ingres’s 1814 painting La Grande Odalisque and Titian’s 1534 painting Venus of Urbino, but Manet includes the eroticism in Olympia that Ingres included in both La Grande Odalisque and The Turkish Bath.

In Olympia, Édouard Manet depicts a prostitute reclining on a bed. Both La Grande Odalisque and Olympia depict women who are used for sex. The odalisque is a concubine in a harem in the Near East while French men pay Olympia for sex. She looks directly at the viewer, and — unlike La Grande Odalisque — we can see the entirety of her breasts just as we can see the frontal nudity in The Turkish Bath.

Manet is also not idealizing this woman. She has dark brown hair. She has an asymmetrical face. She does not have the coyness of La Grande Odalisque or Venus of Urbino. She returns the male gaze and takes the dominant position in the painting, but — even though Ingres popularized this more sensual style — the French art establishment did not approve of Manet’s work. Rather, his painting elicited great controversy at the 1865 Paris Salon. It led to more uproar than perhaps any other painting in a Paris Salon because of its confrontational eroticism.

Modern Acceptance

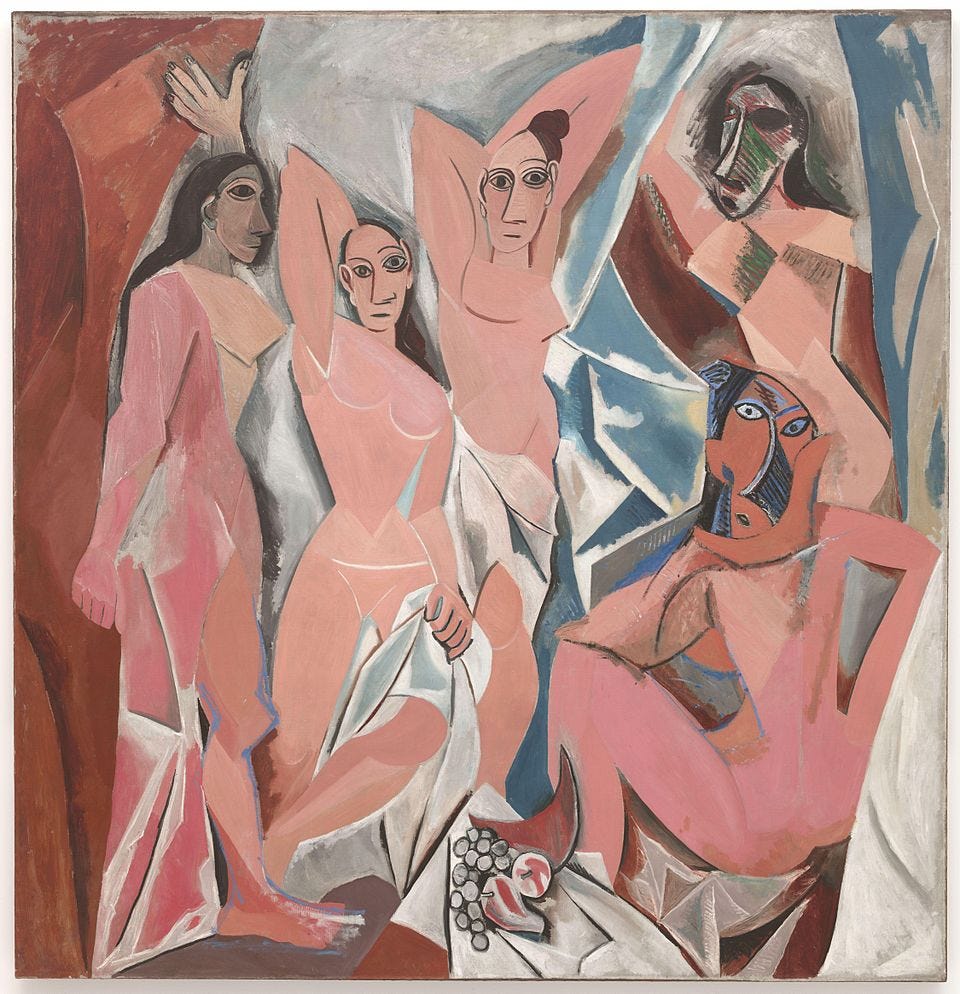

Ingres’s work received full retrospective appreciation in the early 20th century with the beginning of the modernist era. He influenced the more sensual and distorted forms in the paintings of Henri Matisse, Edgar Degas, and others — but I am going to focus specifically on Pablo Picasso at the conclusion of this essay. The image above shows Picasso’s 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, perhaps Picasso’s most influential painting. It marks the inflection point at the beginning of Cubism as it is a Proto-Cubist piece.

Picasso is returning to Ingres’s depiction of concubines and Manet’s depiction of a prostitute. The Cubist painter is depicting five prostitutes in a brothel in Barcelona, Spain. The French salon criticized La Grande Odalisque for its distorted, elongated form — but, now, Pablo Picasso is fully distorted these women’s forms in a fragmented and geometric manner.

Moreover, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres serves as the final great example of the French Art of Comeback alongside Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and his mentor Jacques-Louis David. Now, I can finally return to my series of The Art of the Comeback after my literal artistic detour. In my next piece, I will analyze the comeback of French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau.

The Kingdom of Westphalia is in the northern part of modern-day Germany.