Florida Man's Love Letter to France

The French Art of the Comeback, Pt. I: 19th century comebacks

Introduction

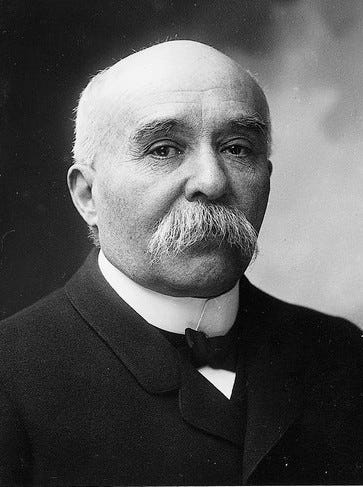

This piece is a prelude to my next piece in my “The Art of the Comeback” series. I am ranking the greatest comebacks in the history of global democracy. My next pick will be Georges Clemenceau, who served two separate tenures as prime minister of France. He first served as prime minister from 1906 to 1909 before the outbreak of World War I. In 1909, members of the French Chamber of Deputies pushed him out because of political scandal, but they chose to bring him back in 1917 to help lead an ailing France to victory in World War I. He served his second tenure until 1920.

I have already ranked the bottom four on the eventual list of ten political comebacks in the history of global democracy. I have listed them below with links to each of their respective Substack articles of mine.

#6: Georges Clemenceau (Prime Minister of France)

#7: Donald Trump (President of the UNITED STATES)

#8: Benjamin Netanyahu (Prime Minister of ISRAEL)

#9: Lula de Silva (President of BRAZIL)

#10: Mahathir Mohamed (Prime Minister of MALAYSIA)

In this article, I will not delve into Georges Clemenceau himself yet. Rather, I want to provide a broader context of modern French history before I analyze Clemenceau’s demonstration of the Art of the Comeback. I initially was going to try to include the analysis of Clemenceau at the end of this article, but I realized that doing so would make it way too long. Those two sections of the article are independent enough from each other to warrant two shorter articles. To reveal everything behind the curtain of my own writing, my biggest struggle likely lies in writing too much. It’s probably better to split up a larger article into multiple smaller and more digestible ones when I can do so.

Beyond the issue of length, France deserves more attentive analysis than the other foreign countries that I have already discussed in this series: Israel, Brazil, and Malaysia. For reasons that I will explain, French modern history has very strong parallels to American history, all of which lies in the context of “modern” world history. Up until this point, I have been analyzing individual men who have demonstrated mastery of the Art of the Comeback: Donald Trump, Benjamin Netanyahu, Lula da Silva, and Mahathir Mohamad.

For these reasons, I am creating a parallel sub-series about France’s specific art of the comeback in their history. French history is just so dense with so many great examples. In this specific article, I will focus on political comebacks, specifically, the House or Bourbon, Napoleon I, and Talleyrand. I will also compare France in the past 250 years to the United States as I point out that our histories are much more intertwined than most people in the 21st century think.

As I started my research and writing regarding Clemenceau, I realized that Clemenceau’s comebacks go beyond himself as a man. Instead, they lie within the broader context of French history in the past three centuries. If I truly want to dissect the Art of the Comeback to the fullest extent, I must dedicate some time to France.

France’s Unmatched Mastery of the Art of the Comeback

French history might have my favorite stories of comebacks in modern history. Napoleon I’s comeback for the Hundred Days might comfortably sit at the top spot for a long time, but that wasn’t democratic. I have chosen to rank French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau at my #6 spot for the greatest comebacks in the history of global democracy. His comeback in 1917 had a massive impact on the rest of the world after he saved France from the throes of defeat in World War I and made France one of the superpowers in Europe after the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 and before Nazi Germany invaded France in 1940.

Before I delve further into Clemenceau, I want to analyze the chaotic context of French history in the modern age. Many historians even mark the French Revolution in 1789 as the beginning of “modern” history, at least in a Western sense. France truly has had a strange penchant for reinventing and resurrecting itself for the past three centuries. The French people have lived as a nationality for a long time, much longer than the idea of “Americans” has, but how have the histories of the French people and the American people differed since the countries’ two revolutions? Of course, I speak of the American Revolution starting in 1776 and the French Revolution starting in 1789.

Stability in the United States

Since the American Revolution, the United States has only had two major constitutions. The United States first had the much looser Articles of Confederation from 1781 to 1789 and, then, the much more centralized United States Constitution, which replaced the Articles of Confederation in 1789. The United States Constitution has governed our country ever since. Sure, it hasn’t stayed exactly the same since 1789. In 1791, the United States added the Bill of Rights with the ten original amendments.

Article V gives Americans instruction on how to amend the Constitution. We have done so 17 times, with the last time in 1992 with the 27th Amendment. One could even argue that we amend it all the time with the process of judicial review on the Supreme Court, but the corpus stays the same. In that way, the United States has similarities to Britain’s “unwritten” constitution, buttressed by centuries of norms and judicial precedents that the British have somehow harmoniously agreed to follow after several internal conflicts. Even if we have an “activist” bench in the United States, our changes pale in comparison to what has happened in France in the same time period.

Chaos in France

In the same timeline across the Atlantic Ocean, the French have had a much more chaotic time following their revolution in 1789. Remember that the U.S. only had two separate governmental systems with the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. Here are all the different governmental structures that France has had in that time:

Bourbon Monarchy (1589-1792)

First French Republic (1792-1804)

First French Empire under Napoleon I (May 1804 — April 1814)

King Louis XVIII (April 1814 — March 1815)

Return of Napoleon I (March 1815 — June 1815)

Bourbon Restoration (1815-1830)

July Monarchy under Louis-Philippe (1830-1848)

Second Republic (1848-1852)

Second Empire under Napoleon III (1852-1870)

Third Republic (1870-1940)

Nazi occupation (1940-1944)

Provisional Government under Charles de Gaulle (1944-1946)

Fourth Republic (1946-1958)

Fifth Republic (1958-present)

France presents us Americans with another alternate universe. In our early history, we had more parallels with France even though we see our “special relationship” now with the United Kingdom. We both had revolutions very close in time in the broader context of the Atlantic Revolutions, which also includes the Haitian Revolution. That revolution in the French colony in Sainte-Domingue came approximately a decade after the conclusion of the American Revolution, and it coincided with the French Revolution. Sainte-Domingue was fittingly revolting against France, its colonial power at the time.

The Enlightenment undergirded these three revolutions. The French Revolution likely would not have happened so quickly or so fervently if we had not successfully won independence from Britain in our revolution. Britain did not have this rebellious disposition that both France and the United States had. The Founding Fathers despised Britain but loved France.

The Literal French “Art” of the Comeback

This love for France especially applied to Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine. Thomas Jefferson brought Neoclassical architecture to the United States. Above, you can see the Panthéon, completed in 1790. The Panthéon exemplifies French Neoclassical architecture while Thomas Jefferson’s Rotunda at the University of Virginia exemplifies the American Neoclassical architecture, which he brought from his time and studies in France. At his University of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson wanted to veer away from the British Colonial architecture at his own alma mater of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. Jefferson opted for the Enlightenment ideals of the country that led the United States to victory against Britain in the American Revolution.

This use of Neoclassical architecture again serves as an example of the Art of the Comeback in France, and it is literally an art! Neoclassical architecture is a return of Italian Renaissance architecture, which — in itself — constitutes a comeback of Classical Greco-Roman architecture. France — and, later, Thomas Jefferson and the Americans — wanted to extol the Enlightenment ideals of scholarship, rationality, and republicanism — all evocative of the Italian Renaissance, ancient Greece, and ancient Rome.

To return to the other American men whom I mentioned alongside Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin served as the U.S.’s first minister to France from 1779 to 1785 while Thomas Jefferson succeeded him. Jefferson served in the role from 1785 to 1789. Thomas Paine even lived in France for 11 years from 1791 to 1801! Amid the French Revolution, he even served in the French National Convention from 1792 to 1795! He even served prison time in France. During the Reign of Terror, Maximilien Robespierre — leader of the Jacobins — imprisoned Thomas Paine because Robespierre viewed Paine as too moderate. Paine served time in prison in France from December 1793 to November 1794, following the demise and eventual death of Robespierre.

The Art of the Comeback by the Bourbons and Bonapartes

The mercurial nature of modern French history sets the stage for comebacks. We saw it with Napoleon I. The Bourbons came back after the fall of Napoleon I. After the fall of the Bourbons and Louis-Philippe’s stint as “Citizen King”, France would enter a brief four-year period of purported republicanism. Despite the best efforts of French leaders, France still hungered for a strong monarchical leader. The Second French Republic, which came after the First French Republic during the Revolution, could only survive four years until President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte declared himself as emperor and established the Second French Empire after the fall of his uncle Napoleon I.

As we see, families love making comebacks in France. The Bonapartes made a comeback after 33 years. The Bourbons made two comebacks. First, Louis XVIII — the brother of the guillotined Louis XVI — brought the Bourbons back to power for a brief ten months during Napoleon I’s exile on the island of Elba. Napoleon I returned for his Hundred Days and deposed Louis XVIII and the Bourbons once more for France. After Napoleon I’s embarrassing defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, his rivals the Allies (Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia) exiled him for the final time to St. Helena. At that point, Louis XVIII and the Bourbons made their final comeback to the throne in July 1815. Louis XVIII reigned until Louis XVIII’s death in 1824 when Charles X — the younger brother of both Louis XVI and Louis XVIII — took over. Charles X reigned from 1824 to 1830 until the success of the French people’s July Revolution when they installed Louis Philippe I, the Citizen King as King of the French.

The Art of the Comeback by Talleyrand

Beyond men in political leadership, such as the Bourbon and Bonaparte families, certain influential individuals behind the scenes have performed the art of the comeback. In this article, I am going to end with one politician — Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (also known as Talleyrand). In my next article, I will look at one French painter, literally an artist, who exemplified not only the Art of the Comeback but the FRENCH Art of the Comeback: Jacques-Louis David. This artist very much matches the story of Talleyrand even though David was just a painter and not a politician.

Born as an Elite

As a political actor in France in the late 18th century and early 19th century, Talleyrand embodies all periods of French political chaos from the 1780s to the 1830s. He was born to an aristocratic family in 1754 in the middle of the 69-year reign of King Louis XV (r. 1715-1774) and the full power of the ancien régime in France. He died in 1838, in the middle of the reign of Louis Philippe I “The Citizen King”.

At age 25, in 1779, Talleyrand was ordained as a Catholic priest. Because of his position as a member of the clergy in France, Talleyrand was a part of the First Estate, reserved for clergymen. The three Estates dominated French societies during the ancién regime. The First Estate comprised one percent of the French population. The Second Estate consisted of land-owning nobility, two percent of the population. The Third Estate (and the least powerful estate) consisted of everyone else, comprising a whopping 97% of the population. By far, the First Estate had the highest proportion of the French population but had the least amount of power as opposed to the clergy and the nobles.

Membership in the Estates General

As Talleyrand ascended to prominence in the Catholic Church, King Louis XVI appointed to him as the Bishop of Autun in 1789. Once a priest becomes a bishop, he immediately transcends the role of just pastor of a flock. He now must foray into politics, especially, in France in the late 18th century. King Louis XVI would give Talleyrand his first elected political opportunity when Louis XVI assembled the Estates General, composed of representatives of each of the three aforementioned estates.

Louis XVI assembled this body because of France’s massive debts. The First and Second Estates were not paying enough taxes to support the French government’s expenditures. Louis XVI thought that he could get buy-in from each of the three classes of French society if he gave them advisory power through a deliberative body in a state otherwise known for his adherence to absolute monarchy in contrast to its peer in Britain. A representative from any given estate had to earn the vote of his peers within the estate, so Talleyrand had to earn the support from his fellow clergymen. He succeeded in that effort.

As a member of the clergy, Talleyrand initially supported the Bourbon monarchy in France, but did he really support it? This question underlies Talleyrand’s entire political career. Instead of truly pushing for reforms in which he believed, Talleyrand licked his finger and stuck it in the wind. Talleyrand was malleable. The mercurial mood of the French people at a given time informed his judgment. During the beginning of the French Revolution, Talleyrand played it safe. He wanted everything both ways. He supported a revolution to weaken and, eventually, overthrow the monarchy, but he wanted to be moderate about it. The Enlightenment? That’s great! Everyone is doing it! But let’s not get too crazy.

Departure from the Catholic Church

Talleyrand could see that momentum was forming for the Third Estate, the 97% of the French population. Sure, the French monarchy and clergy can try to suppress the influence of commoners by vastly diluting their vote in the Estates General, but — at a certain point — it’s a math problem. Ninety-seven percent of the population have the ability to wreak havoc on the three percent at the top. Talleyrand acknowledged this fact and supported the Third Estate even though he technically represented the First Estate. More specifically, Talleyrand led the nationalization of church property through the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. This law in France also mandated that priests declare loyalty to France before loyalty to the Catholic Church in Rome.

With these measures, Talleyrand betrayed the Church. He was one of only four bishops who took an oath to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Sure, lower-level clergymen were pledging loyalty to them, but it’s different when a bishop does. A bishop must report to Rome even if he is serving in France. Talleyrand used his power within the revolutionary government to allegedly consecrate two constitutional bishops. The adjective “constitutional” in this context refers to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Due to all these deviations from the Catholic Church, Pope Pius VI ultimately excommunicated Talleyrand, who then left the Church. He instead entered secular life as many people did amid the French Revolution.

Foreign Minister under the Directory

After the demise of the Reign of Terror and Maximilien Robespierre in the Thermidorian Reaction, a new constitution established the Directory in November 1795. The Directory consisted of five men who served as the executives of the French government. They also had the bicameral legislature that included the Council of Five Hundred (the lower house) and the Council of Ancients (the upper house). This system was still embodying the constitutional republic that French citizens purported to want during the French Revolution.

Under the Directory, Talleyrand served as France’s Foreign Minister between 1797 and 18071. Talleyrand used his high position to support Napoleon Bonaparte’s eventual military campaigns. Beyond exercising political power, he gained from the general corruption of the Directory. He received many personal bribes as foreign minister.

Napoleon’s French Empire

As Napoleon Bonaparte amassed political power in the late 1790s during the existence of the Directory, Talleyrand again made a shift in loyalty. Talleyrand keeps appearing in all of these different periods of French history. He was like a wart that keeps re-emerging even after you have frozen it a dozen times in the past six months. Talleyrand maintained political power under Napoleon I until he changed loyalties once more in 1807. As Napoleon I escalated his military campaigns across Europe, Talleyrand saw Napoleon’s emerging recklessness as a military commander.

Sure, in 1807, Napoleon I was coming off two major victories. At the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt in October 1807, Napoleon I defeated the Prussians and destroyed their army. He compelled Prussian King Frederick William III to flee to Russia for support. Napoleon I had ended Prussia’s dominance as a great power in Europe. After Napoleon I led the French to victory over the Russians and Tsar Alexander I at the Battle of Friedland in 1807, Russia too had to subject herself to Napoleon’s dominance in Europe. With the Treaty of Tilsit, Russia had to make many concessions to France. Perhaps, most importantly, Russia had to join Napoleon I’s Continental System, which blockaded trade from Britain to continental Europe, hence the use of the adjective “continental”.

Despite these victories by Napoleon I, Talleyrand saw them as harbingers of a future demise. As Icarus did, Napoleon I was flying too close to the sun, and his hubris would lead him to soon fall flat on the ground. Consequently, Talleyrand left Napoleon's government in 1807, the same year in which Napoleon triumphed in the aforementioned Battle of Friedland against Russia. Talleyrand was a smart political actor. He could see what was coming down the pike, and he was eventually right.

Near the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon I was losing major battles. He had a failed invasion of Russia in 1812. He lost at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 against Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Sweden. The Allies then took advantage of Napoleon’s newly emergent vulnerability at an invasion of Paris in March 1814. Behind the scenes, Talleyrand was even conspiring against Napoleon I with the France’s enemies in the Allied Powers. He helped them with their ultimately successful invasion of France. As he done before, Talleyrand could foresee who was gaining steam, and he sided with them. In the process, he abandoned the man to whom he once swore full fealty.

The First Bourbon Restoration with Louis XVIII

After Paris fell to the Allies and the Allies exiled Napoleon Bonaparte to Elba in April 1814, the Bourbons briefly returned to power in France. Louis XVIII — the younger brother of the executed Louis XVI — took the throne in May. With the return of the Bourbons in France, Louis XVIII appointed Talleyrand as his Minister of Foreign Affairs. Again, Talleyrand made a comeback to power in the government based on his Machiavellian conspiracy with the Allies against Napoleon I. Talleyrand began serving in this post in May 1814.

Talleyrand’s uncanny French ability to make comebacks can operate as a double-edged sword. During Talleyrand’s political career in France, the country obviously was undergoing tumultuous and rapid changes in power. In this scenario, to maintain your own power, you must switch allegiances frequently as Talleyrand did, but you can only flip-flop so much. At a certain point, the people in power in your country at any given moment will begin doubting your loyalty.

Let’s say I am Louis XVIII. Of course, I am happy with Talleyrand’s contributions to Allied efforts to topple Napoleon and to exile him to Elba. Without Talleyrand, I might not have risen to the French throne! My beloved Bourbons would still be out of power! Regardless, Talleyrand’s successful conspiracy against Napoleon shows distrust. Why did Talleyrand so rapidly go from fully supporting Napoleon’s rise to emperor to conspiring with foreign countries to oust him from France? This fact implies that Talleyrand has no true loyalties beyond what will maximize his power and status at a given moment. What happens if I as King Louis XVIII can no longer personally benefit Talleyrand? Won’t he just betray me as he did to Napoleon I?

During Louis XVIII’s brief first reign, he had to begin as a moderate to ease France into absolute monarchy again. With respect to the issue of monarchy, Talleyrand was a moderate, but Louis XVIII and other royalists were trying to veer back toward a stronger monarchy in France. Talleyrand might have threatened that goal. Furthermore, on the global stage as Foreign Minister, Talleyrand was advocating for France at the Congress of Vienna, which attempted to set the stage for a post-Napoleonic Europe. Even though Talleyrand was successfully advocating for French interests, Louis XVIII thought that Talleyrand might have been acting too independently. In the mind of Louis XVIII, Talleyrand’s efforts geopolitically could serve Talleyrand’s personal Machiavellian goal for power. Because of these issues with Talleyrand, Louis XVIII dismissed him from his post as Foreign Minister in February 1815.

Napoleon’s Hundred Days

Louis XVIII’s first reign lasted only ten months because Napoleon Bonaparte escaped Elba and invaded Paris in March 1815. The French people and even French soldiers under Louis XVIII welcomed Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Bourbons had lost power once more in France. Louis XVIII fled to Ghent, part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands at the time. Today, Ghent is in Belgium.

As the French emperor once more, Napoleon I invited Talleyrand to support him in the new government, but Talleyrand maintained his loyalty to Louis XVIII and the Bourbons. Instead of joining the new person in power, Talleyrand publicly denounced Napoleon’s return. At this time, Napoleon I would frequently compare Talleyrand to Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed Jesus Christ.

Second Bourbon Restoration

Among all these chaotic periods of French history in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Talleyrand perhaps had the least influence during the Second Bourbon Restoration. After Napoleon I’s disastrous defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815, he left the French throne once more. Napoleon I abdicated and left power for the final time. Louis XVIII then returned to power with the support of the Allies.

Upon Louis XVIII’s return, Talleyrand did briefly return to power as the French prime minister, but he only served for a little under three months in 1815 from July 9 to September 26. Again, ultra-royalists in Louis XVIII’s new government distrusted Talleyrand because of his connections to past revolutionary movements. His dismissal in Louis XVIII’s second reign very much mirrored the factors for his dismissal during Louis XVIII’s first reign. At the end of the day, again, Talleyrand’s art of the comeback often served as his downfall. Comebacks oftentimes require that you switch allegiances to different people and different factions in your country’s politics.

Unlike Napoleon, Talleyrand never lived in exile during the times when he did not have power, perhaps, because Talleyrand did not present any continental threat of war as Napoleon did to other European states. Talleyrand lived in Paris as a private intellectual although he did host political salons in the city, but he would get one final bite at the apple when the Bourbons finally fell amid the July Revolution in 1830.

Louis-Philippe’s July Monarchy

In July 1830, common Frenchmen united to rebel against the Bourbon monarchy, led at the time by Charles X (the younger brother of both Louis XVI and his direct predecessor Louis XVIII). The painting shown above — Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix — shows an account of the violence and emotion in this revolution. Of course, this piece — painted the same year as the July Revolution in 1830 — includes fantastical elements, primarily the bare-chested French personification of Liberty “leading the people” to overthrow the Bourbon monarchy. After the rebels prevailed in the July Revolution, the Bourbon king Charles X abdicated amid the violence and fled to Britain. He later went to Austria and died there in 1836.

Marquis de Lafayette — a French war hero of the American Revolution five decades prior — served as a symbolic leader of the July Revolution even though he was too old to do actual military commanding. After Charles X’s abdication and eventual fleeing from France — Lafayette and many other leaders supported selecting a nobleman named Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, to lead the new July Monarchy. The rebels despised the House of Bourbon. Even though Louis-Philippe came from the House of Orléans, an offshoot of the Bourbons, people knew him as a man who supported liberal reforms in France. Perhaps, most importantly, Louis-Philippe’s genealogical branch supported the French Revolution and the execution of King Louis XVI four decades prior.

Nevertheless, in some ways, Louis-Philippe came out of nowhere despite his noble heritage. How could he attain legitimacy in France? Elevating Talleyrand to the position of ambassador from 1830 to 1834 to the U.K. gave legitimacy to Louis-Philippe. Perhaps the position of ambassador didn’t directly offer the legitimacy, but a respected statesman and diplomat was supporting this new French government. After wandering in the political wilderness of France for 15 years, Talleyrand made his final comeback. He only served in the ambassador post for four years under Louis-Philippe, but he had reached the age of 80 by 1834. He retired and ended his storied political career in peace. However, Talleyrand is just one French man out of many who exemplify the FRENCH ART OF THE COMEBACK.

Talleyrand had a brief break in his tenure here from July 1799 to November 1799.