The "French" Art of the Comeback, Pt. II: David's Subservience to French Monarchy

Florida Man vs. Jacques-Louis David and French Neoclassicism

Introduction

Amid my drafting of my series “The Art of the Comeback” — a ten-part series of articles that rank the most significant political comebacks in the history of global democracy — I went on a French detour. I got to writing my #6 spot for Georges Clemenceau, the prime minister of France twice: 1) 1906-1909 and 2) 1917-1920; but I realized that I cannot limit my visit to France just to Clemenceau. So many other characters in French history demonstrate The Art of the Comeback. In the past three centuries, the French might have the greatest penchant for the Art of the Comeback.

On May 16, I released the first installation of this French sub-series “Florida Man’s Love Letter to France”. In that article, I explored political comebacks that preceded Georges Clemenceau. None of these comebacks were democratic. They preceded France’s long-term state of republicanism after Emperor Napoleon III abdicated in 1870 in favor of the Third French Republic. The leaders whom I analyzed included: Napoleon I, Talleyrand, and King Louis XVIII (who served as an avatar for the resurgence of his entire Bourbon family).

In this article, I veer away from pure politicians. Instead, I will analyze French painters, literal artists — and, yes, they exemplify the Art of the Comeback just as much as the political leaders do. Especially, in France, art is inextricable from politics. I will be analyzing three painters in France amid these chaotic times. These people shifted loyalties just like Talleyrand. They fell in and out of favor under different regimes. I will be analyzing the following in this order:

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825)

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842)

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

I will start with Jacques-Louis David.

Historical Background Before David’s Rise

Rising to prominence as a young artist in the 1770s, Jacques-Louis David was coming of age in a time of extreme change for French politics and, by extension, art — but that isn’t saying much! It seems like France is always in a period of extreme change, especially, in the 18th century! I always saw this chaos in the 18th century as ironic when you consider the long reigns of the Bourbon kings during this period. You would think that France would have the cultural stability of the dynasties in ancient Egypt, or perhaps it is recency bias. We are more likely to split hairs in French history because it is much more recent as opposed to three millennia ago in Egypt.

As for the long reigns, Louis XIV reigned for 72 years from 1643 to 1715. He reigned for so long that he outlived his son and grandson who would have otherwise inherited the throne if Louis XIV had not taken the throne so young and lived so long. Louis XIV took the throne at age 5 and lived until age 76. Consequently, Louis XIV’s great-grandson Louis XV inherited the throne. Louis XV reigned for 59 years from 1715 to 1774. He ascended to the throne at 5 years old, the same age as his great-grandfather. Louis XV then died and, consequently, left the throne at 76 years old.

These two reigns brought in two very different styles of art and architecture although both were veering toward the French monarchy’s excess, which ultimately culminated in the French Revolution. Louis XIV and Louis XV did arguably lead to the unfortunate execution of their great-great-grandson and grandson, respectively. In a word, the art commissioned by both Louis XIV and Louis XV led to decadence, albeit for different ends.

Louis XIV and Before

Sure, Louis XIV wanted excess, but he saw his excessive art as strengthening the absolutist monarchy and, by extension, France (or at least in his mind). In the 1660s, Louis XIV began building the opulent and decadent Palace at Versailles in Versailles, France, approximately 13 miles from the central capital city of Paris. Above, I show an image of the exterior and an image of the Hall of Mirrors inside the structure. Louis XIV was employing the Baroque style, which had dominated European art since the end of the Renaissance and around the beginning of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Everything is BIG. Everything is BRIGHT. Everything is GOLD.

Louis XIV wasn’t doing anything new. He was just a product of his environment! The Bourbon monarchy had been using the commoners’ money to commission ornate art for decades and decades! He could look back to what his grandmother Marie de’Medici did. In 1621, a decade after the death of her husband King Henri IV (and Louis XIV’s grandfather), Marie de’Medici commissioned master Baroque artist Peter Paul Rubens to create 24 paintings depicting her in different points of her life. She displayed them in a gallery in the royal residence of Luxembourg Palace in France.

The top image above shows them today on display in the Louvre Museum. The bottom image above shows perhaps the most notable of the paintings, Henri IV Receives the Portrait of Marie de’Medici. This painting depicts the ancient Roman deities of Jupiter, Juno, Hymen, and Cupid presenting a portrait of Marie de’Medici to King Henri IV as if she were coming down from the heavens. This piece exemplifies how these French monarchs viewed themselves. When we see these attitudes on full display in art paid by taxes, we can understand why we had a French Revolution.

Louis XV and Rococo

Louis XIV’s successor Louis XV saw the Baroque style’s evolution into Rococo as did Jacques-Louis David, who was attending art school in the 1760s and 1770s. Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s 1767 painting The Swing exemplifies the Rococo style. Louis XIV was using art to bolster an absolutist monarchy and, to a degree, a Catholic culture in France. During the Rococo period, painting lost its sharp form and increased in its frivolity.

Fragonard’s painting has zero moral value to it. It simply depicts a woman riding a swing with one man pushing her and another man looking up her skirt. Although we do not see any nudity, the woman kicking off her shoe implies that she is disrobing for sexual intercourse with one of the men. Or maybe both!

We would not see overtly sexual pieces in a significant way until the time of Édouard Manet. He famously depicted unidealized, realistic nude women in the French Realist movement. Pieces, such as his 1863 pieces The Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia exemplify this eventual trend in French painting. I show The Luncheon in the Grass above. It has clear erotic themes. Again, we have two men with a female subject in a green forest. Perhaps it is what would happen a few minutes after the moment depicted in The Swing.

David’s Subservience to the Monarchy

Jacques-Louis David would not have risen to artistic prominence without the support of the Bourbon monarchy, but no respected artist would have. All proper artistic education in France went through academies supported by the monarchy. David studied at the Royal Academy and began shifting toward Neoclassicism, burgeoning in France at the time. His teacher Joseph-Marie Vien pioneered the Neoclassicism movement as many artists began seeing the Rococo style embodied in The Swing as too decadent and structureless. Proponents of Neoclassicism chose to return to the styles of classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. Art should promote virtue — not hedonism — as seen in The Swing.

At age 27, in 1774, Jacques-Louis David earned the Prix de Rome, awarded by the French monarchy to the most talented young artist in France each year. With the prize, the artist would do a residency in Rome for three to five years to learn the techniques of classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. Louis XIV began the Prix de Rome in 1663 to support French artists, who primarily would later serve the royal court.

Winning the Prix de Rome gave a massive amount of attention to David in the art world, and he eventually began painting for the monarchy. Louis XVI’s Director of Royal Building and cultural minister — Comte d’Angiviller — commissioned Jacques-Louis David to make a painting that promoted civic virtue. Louis XVI’s monarchy wanted to break away from the decadent Rococo art created under Louis XV’s regime. David’s 1784 painting The Oath of Horatii accomplished that goal, at least, for a little while.

Louis XVI wanted to use the emerging Enlightenment movement to reform French monarchy without allowing for complete revolution, and a return to classical art communicated that goal. The monarchy thought that Neoclassical art would appease the French citizens sympathetic to the Enlightenment. So much of the Enlightenment came from idealizing Greek and Roman philosophy and culture. The Enlightenment thinkers valued rational, civic virtues — and Neoclassical art attempted to value these Roman virtues as well. David did so in two ways in The Oath of the Horatii: 1) its subject matter and 2) its form.

Subject Matter of The Oath of the Horatii

The painting depicts a legend from ancient Roman history, a major focus of interest for Enlightenment thinkers and Neoclassical artists. The three Horatii brothers of Rome are swearing an “oath” to their father to battle three other brothers from the rival city state of Alba Longa. The rivals were the Curiatii brothers. Whichever side won would settle a war between Rome and Alba Longa. Three women sit on the right side of the painting. The woman furthest to the left in the green gown is likely a nursemaid caring for two of the children of one of Horatii brothers.

The woman in the middle is named Camilla, a sister of the Horatii brothers, but she is engaged one of the Curiatii brothers. The woman furthest to the right is Sabina, a sister of the Curiatii brothers, but she is married to one of the Horatii brothers. Consequently, regardless of which side wins the duel, someone in the Horatii family is also losing, yet the brothers are swearing an oath to defend Rome to the death anyway. Their willingness to do so exemplifies the civic virtue that Louis XVI and Jacques-Louis David wanted to communicate. The Horatii brothers were overcoming personal emotion and family for the larger cause of Rome. In the context of 18th-century France, Louis XVI wanted The Oath of Horatii to show French citizens the patriotism that they must display.

Form of The Oath of Horatii

Comparison to Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper

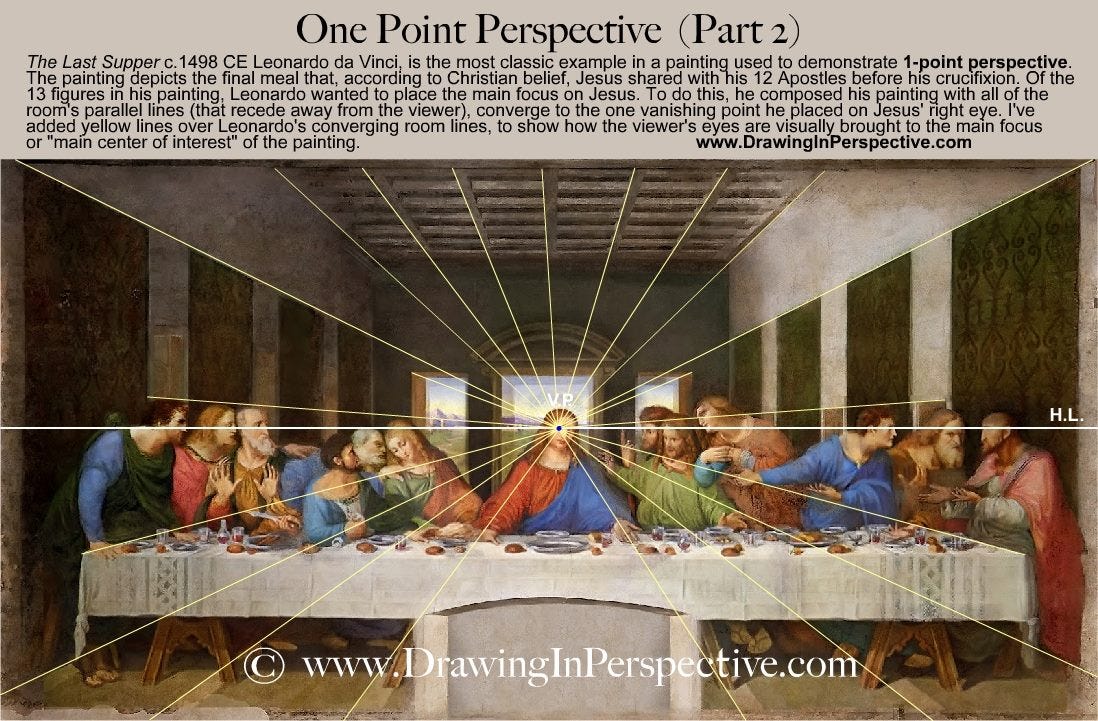

In The Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louis David does not just depict Roman subjects, but he also returns to classical forms too. He more specifically employs conventions from the Italian Renaissance. The image above displays the painting Last Supper, one of the best early examples of the use of one-point linear perspective by Italian Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci.

One-point linear perspective employs orthogonal lines that converge at a vanishing point on a horizon line. Pioneered in the Italian Renaissance, this technique creates naturalistic depth in a painting. The image above shows orthogonal lines superimposed on an image of Last Supper. As you can see, the orthogonal lines converge at the center of Christ’s head.

The use of linear perspective contrasts with the techniques of painting or any two-dimensional art in the Middle Ages. The image above shows Marriage of the Virgin, one of the many scenes in Giotto di Bondone’s frescoes in the Arena Chapel in Padua, Italy. The walls of the chapel’s interior have cycles related to the lives of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. The image shown above depicts one of the scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary, particularly, her marriage to Joseph. Medieval paintings, such as this one, have no linear perspective. The dimensions of rooms and the placement of human figures look crowded with no realistic depth.

Although painters were using linear perspective after the Renaissance and before Neoclassicism, Jacques-Louis David really emphasized his use of it in The Oath of the Horatii. You can visibly see the orthogonal lines in the painting with the square tiles on the floor and the bricks on the wall to the right. Leonardo emphasizes his orthogonal lines in Last Supper with the rectangular coffered ceiling and the outline of the doorways on the walls in the dining room. Jacques-Louis David and the French government wanted to make it CLEAR that they were honoring the rationality of Leonardo da Vinci and the Italian Renaissance.

Comparison to Raphael’s School of Athens

Jacques-Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii employs something else that refers to both the Italian Renaissance and classical antiquity. David uses certain architectural features demonstrative of those eras. Raphael’s 1511 fresco School of Athens illustrates the use of architectural settings in paintings characteristic of the Italian Renaissance. In ancient Greece and Rome, the architectural features were in the actual buildings. Beyond the architecture, Raphael also exemplifies the use of linear perspective in his painting in the same way that Leonardo did.

Raphael’s School of Athens uses arcades that recede into the back. The arches have coffers, similar to what we see in Last Supper. Raphael also painted pilasters with Doric capitals, one of the three Classical orders of columns. A pilaster is just a rectangular column. Regular columns are cylindrical. David uses the same Doric capital order in The Oath of the Horatii. We can see columns that support an arcade behind all the human figures. Doric columns support that arcade.

Moreover, all these choices of subject matter and form demonstrate Jacques-Louis David’s allegiances at this point in his artistic career. Soon, the winds will change with the French Revolution, and David’s allegiances (along with his artwork) will change as well.