NOTE: I began writing this review shortly after I saw Inside Out 2 in theaters on June 14, but I began writing on other topics because of the chaos in the political scene over the past month and a half. Regardless, Inside Out 2 made enough of an impact on me that I felt the need to finish the article.

From a media consumption standpoint, Pixar defined my childhood. My upbringing perfectly aligns with the golden age of Pixar. I was born in 1998, the year in which Pixar released its second movie A Bug’s Life. The 2004 film The Incredibles became one of my favorite films, and I still adore it to this day. At age 6 at its release, I loved the superhero aspect, but — as an adult now — there are many more adult themes in it that I appreciate even more now (e.g. Bob Parr’s dissatisfaction with corporate life and gradual transition from ideal male physique to middle-aged obesity).

If I want to relate Pixar’s output to the course of my childhood, Cars 2 could mark the beginning of my adolescence. I turned 13 the year of the release of Cars 2, which many people deem as the beginning of the end of Pixar. Fittingly, I think that Cars 2 was the first Pixar movie released in my lifetime that I did not see in theaters. I still have never seen it, and I likely never will. Since 2011, I have only seen a few Pixar movies:

Brave (2012 — age 14)

Inside Out (2015 — age 17)

Finding Dory (2016 — age 18)

Incredibles 2 (2018 — age 20)

On Friday, June 14, I broke my six-year streak of never seeing a Pixar movie when I went to see Inside Out 2 in theaters. I am going to dissect the movie further later in the article, but I really did like the movie. However, the movie itself did not prompt me to want to write this article. Over the past few days, I really thought about my choice to see the movie, its relevance to Pixar as a studio, my childhood, and the American cinematic landscape itself.

Proof of Concept:

Synopsis:

Before I delve into my intentions of seeing the movie, I guess that I will give a brief synopsis. You can look at Wikipedia on your own, but I will give you the synopsis from my perspective anyway.

The basic conflict in the movie originates from the fact that the main character from the first film, Riley, is beginning puberty. She was 11 years old in the first film from 2015, and — in this 2024 sequel — she is 13 years old. In the first film, she only has five personified emotions, which she developed as a pre-pubescent child: Joy, Disgust, Fear, Anger, and Sadness. The onset of Riley’s puberty brings four new personified emotions: Anxiety, Envy, Ennui, and Embarrassment.

In the first film, Riley does not really serve as the protagonist. Rather, the personified character of Joy — voiced by Amy Poehler — serves as the protagonist, and she must contend with her antithetical opposite — Sadness — voiced by Phyllis Smith. Once the new emotions arrive in the sequel, the conflict arises from the five original childhood emotions, led by Joy, contending with the post-puberty emotions. They must find an equilibrium and middle ground so that they can help Riley with flourishing during her freshman year in high school.

Why Make a Sequel?

I understand the financial reasons to make a sequel, and I do not begrudge Pixar or Disney for following this pathway. Sequels can pester fans because it implies that the studio has exhausted all original ideas and is cynically drawing the old well from the Golden Age. Pixar (and Disney as a larger conglomerate) is a company that employs people. Their goal is to maximize revenue.

It’s not a smile factory for the purpose of making you happy. It’s a smile factory as long as the smiles are economically feasible and have a high return on investment. In the context of Inside Out 2, Pixar has done very well. It became the highest-grossing Pixar film of all time and third-highest grossing animated film behind 2019’s remake of The Lion King and Frozen II.

However, Pixar has served as an acclaimed artistic entity in our culture for the past three decades. People expect a grander product from Pixar than they do from a studio like Illumination, which has less of a history with critical acclaim. From the perspective of someone critiquing the cinema as an art form, what artistic goal can a sequel achieve beyond grossing the studio beaucoup bucks? Can there be a larger artistic goal? Or does every sequel have the original sin of cynicism? I argue for a middle ground.

Let’s Play Good Sequel, Bad Sequel

A proper sequel with artistic integrity must replicate why people loved and acclaimed the prior film but build upon and bolster the prior story in a creative way. Before discussing Inside Out 2, I will look at two Disney sequels at either extreme, but these two films have one major similarity. They both made a Disney a large chunk of change. (I am going to see how many idioms I can use for money in this article.) For the example of the good Disney sequel, I will point to the 2010 film Toy Story 3, and — for the bad sequel — I point to the 2015 addition to the post-acquisition Star Wars.

Clearly, based on the title, Toy Story 3 was not a sequel to a first film. Rather, it is the third film in the Toy Story franchise. It has the number “3” in it! (Don’t tell George Lucas.) The prior film from 1999 Toy Story 2 is a good story on its own, but I think that Toy Story 3 effectively bookends the arc of the franchise in exemplary fashion. It acts as a perfect coming-of-age conclusion to the series, later sullied by 2019’s Toy Story 4 and 2026’s upcoming Toy Story 5, but I see no reason why we cannot view the first three films in the franchise in a vacuum.

Toy Story 3

Andy, the owner of all the toys, goes to college and must contend with the fact that he is entering adulthood and cannot continue playing with these old toys — but Andy himself does not feature prominently in the film. Although he is the one who “comes of age” in the film, the personified toys themselves must endure and find purpose once their original owner enters young adulthood. In other words, Buzz and Woody come of age just as much as 18-year-old Andy does. Sure, the toys are anthropomorphic pieces of plastic and plush, but the protagonist Woody (voiced by Tom Hanks) finds himself in a place throughout the series to which we — as corporeal humans — can all still relate, specifically, the confusion fomented when we feel unwanted by those we love (or at least think that we love).

Star Wars: A Force Awakens

At the other end of the Disney spectrum, we have Stars Wars: A Force Awakens (or Episode VII). The beginning of this new Star Wars trilogy came three years after Disney had acquired Lucasfilm in 2012 for $4.1 billion. To justify that huge purchase, Disney needed to produce the anticipated Episode VII, which George Lucas had always refused to make. How does one make a new Star Wars trilogy? Disney decided to essentially rehash everything from the first Star Wars from 1977.

Where Does Inside Out 2 Land?

Returning to Inside Out 2, on the onset, I see Inside Out as a compelling premise for a franchise. The exploration of psychology can intrigue viewers, especially through the lens of cute Pixar animations personifying one’s broad menagerie of emotions. Specifically, with Inside Out 2, it serves perfectly as a sequel and does not give the impression of a cynical cash-grab. I think that Pixar knew that they would likely gross a large amount of money from a sequel of a popular film of theirs, but the concept of the sequel makes sense. In fact, it probably has the most justification to exist out of any Pixar sequel since Toy Story 3 from 2010.

Returning to the analysis of sequels, Inside Out 2 and Toy Story 3 serve as the ideal sequels because they take the original premise of each respective series and have character development while they maintain what made the originals great. These two Pixar sequels provide new narratives to old characters whereas The Force Awakens reheated narratives from the original Star Wars film.

In a way, when an original film revolves around a child, it makes it easier for the writers and directors to add this desired character development because they can just take the child and make him or her grow up, go through adolescence, and enter adulthood. Both Inside Out 2 and Toy Story 3 do just that. The coming-of-age narrative will be one of the most effective and powerful narrative tools for the rest of time. I could see how somebody would see it as a cheap narrative trick to see Andy drive off for college and have Woody and Buzz sorrowfully waving off, but it is an important narrative to communicate.

Coming-of-age and adolescence will always occur. Human biology will not change, but society changes. Therefore, the circumstances of how a child becomes an adult will change. That is a story always worth telling. On the other side of the coin, I guess it is harder to write a “coming-of-age” story about a car voiced by Owen Wilson.

Where Pixar Succeeds and Fails

Both the Inside Out and Toy Story franchises show Pixar at its best creatively. Pixar seemingly works best when they can take anthropomorphized characters (toys, monsters, sea creatures) and apply relatable human emotions to them, but — even though I hold this assertion — I rank The Incredibles as my top Pixar film. Despite my high esteem of The Incredibles, Pixar has not had great critical success with largely human-oriented stories.

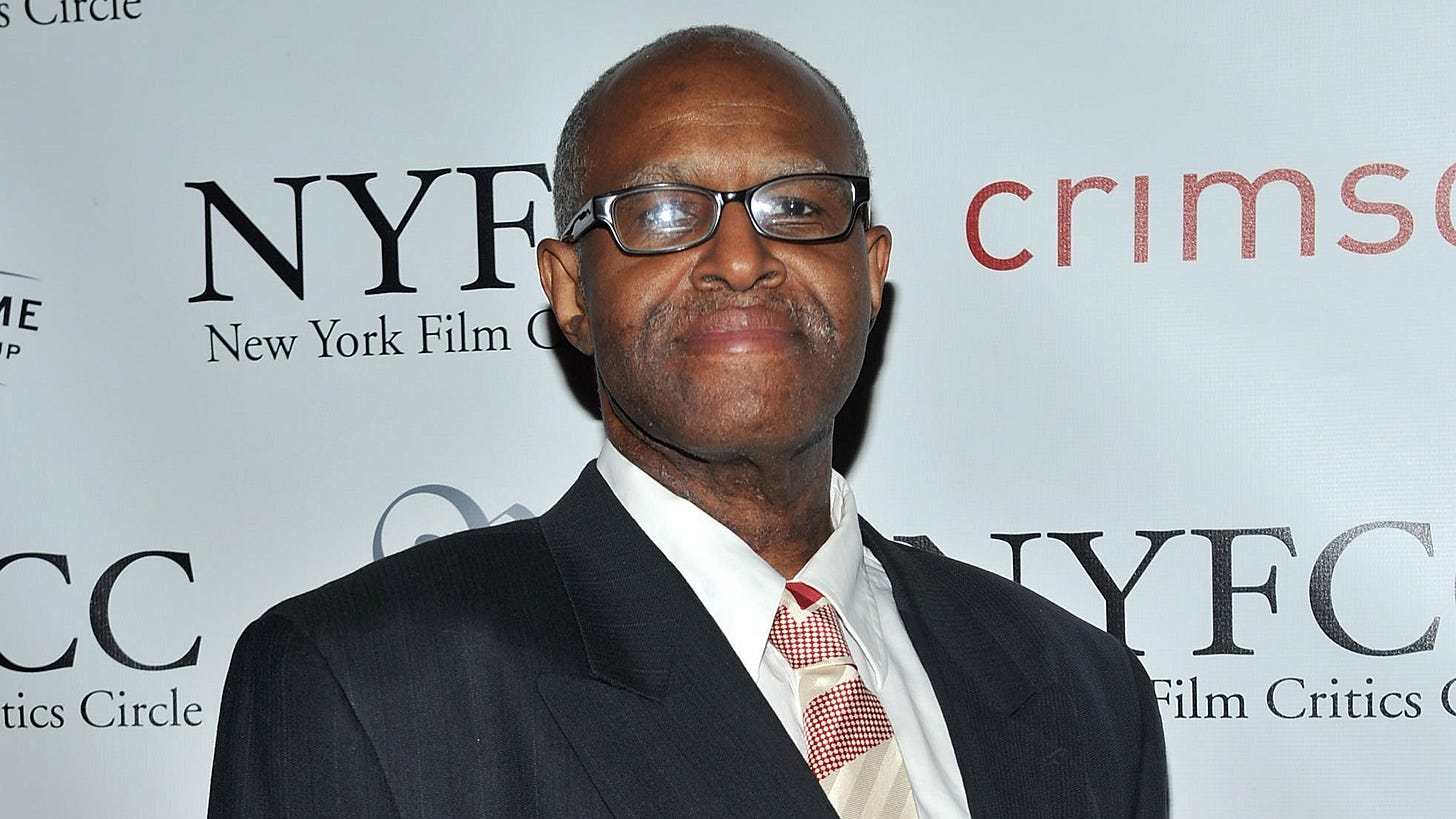

When Pixar solely focuses on normal people, we get sterile scenes in the uncanny valley, such as the one above. This scene comes from Pixar’s 2020 film Soul, which released straight to Disney Plus during the pandemic. Ironically, this scene in the barbershop with the protagonist Joe Gardner seemingly has no “soul”. As I said, it gives us a sense of uncanny valley. It almost looks real. The lighting and the walls, especially, do. By 2020, we get the sense that Pixar could make hyper-realistic images, yet they still have to give these characters somewhat cartoonish features.

All the humans in the barbershop have uncanny valley. The only character with the features of a characteristic Pixar character is the cat, but I get the sense that Illumination Studios could have generated this exact same scene in a film in its franchise The Secret Life of Pets.

Joe in Soul has naturalistic features, which contrast with the more geometric and jagged features of the protagonist Bob Parr (Mr. Incredible) in The Incredibles. The lighting in the still shown as well does not give the sense of uncanny valley. We know we are in a cartoon, partially, because of stylistic choices but also technological constraints based on The Incredibles coming out in 2004, sixteen years before the release of Soul.

We have the added context of Soul coming out during the height of the pandemic when theaters had not fully returned yet, but Inside Out 2 shows a complete bucking of the 2020 precedents. Since its release less than two months ago, Inside Out 2 has become the 10th highest grossing film of all time at a total worldwide gross of $1.6 billion. It also has become Pixar’s highest grossing film once it surpassed the 2018 film Incredibles 2, which had grossed $1.2 billion.

To tie Inside Out 2 to Soul, this 2024 film gives me the most issues when we get those hyper-realistic scenes as we saw in the barbershop with Joe in Soul. The film oscillates between scenes in the external world and the internal world of Riley’s psyche. When I was watching the film, I always preferred the scenes inside Riley’s mind because — once the point of view transferred back to Riley’s external world — we saw that uncanny valley again as we see in the still above.

In contrast with Soul, I think that these human characters of Riley and her two friends have much more of a signature Pixar cartoonish look that does not evoke uncanny valley. I assume that they shifted away from the animation in Soul, but the background in the hockey rink has the hyperrealistic lighting coming through the windows which upsets me visually.

The bright polychromatic visuals of the scenes inside Riley’s mind enticed me much more and showed the power of animation. When Pixar takes me to the barbershop or the hockey rink, they might as well take me to the sterile, fluorescent-lit doctor’s office to get my colonoscopy. It becomes that soulless.

The film also weakens narratively in the external world. I am not critiquing Riley as a character. I get that the true characters are the emotions whose actions manifest in the real world via Riley, who merely serves as a vehicle, but the human characters — especially, the other girls at hockey camp — often come off as NPCs. There are pixellated characters in Pokémon Red & Blue with more life than these people, but I understand that perhaps Pixar did not want to draw too much attention from the emotions by drawing so much attention to Riley from the outside.

How Society Changed Around Riley

The Mathematical Narrative Paradox

Whenever you have a major gap in years between sequels, you run the risk of the cultural context of society changing and affecting the narrative of your film. This issue mostly would rise with animated films because, in live-action films, the actors physically age. That biological fact puts constraints on live-action sequels separated by many years, but — in an animation — the characters only change if the animators want them to change.

The math does not work here. In Inside Out, released in 2015, Riley was 11 years old. Therefore, she would have be born in 2004. In the sequel, she is 13 years old. She would have been born in 2011. She only ages 2 years in the fictional world, but there is a seven-year difference in the two characters’ ages if they were real people. I am not critiquing the premise of the movie. It wouldn’t have made sense to jump to Riley already being 20 in Inside Out 2. The premise of the emotions amid puberty is great, and we do not want so much change that the protagonist becomes unrecognizable.

A girl born in 2004 has had a massively different experience than a girl born in 2011. The 2004 Riley was 16 years old during the pandemic while the 2011 Riley was 9 years old. Those two facts create a giant divergence in the experiences of these two girls. I cannot speak on behalf of the viewpoint of a girl born in those two years, but I think that gap in time will prove to be huge in the real world. Seven years is really not that big of a difference culturally in most instances.

I was born in 1998. I do not feel so culturally separated from someone born in 1992 or 2005. We all grew up with the similar backdrop of the Internet Age and the rise of social media, but I contend that the pandemic massively changed the psyche of children and adolescents during that time. The 2004 Riley is different from me in that I had already completed adolescence during the onset of the pandemic. She would have been a junior in high school, but a junior in high school has advanced enough through adolescence that a paradigm-shifting historical event, such as the pandemic, would not affect the 16-year-old as much as a 9-year-old in the 4th grade. The fourth grader would still be a few years separated from the social and cultural pressures of puberty.

The pandemic completely altered how that 9-year-old interacted socially and fomented a generation much more dependent on screens and social media than those just a decade or so removed, like myself. We can see these effects manifested in Bo Burnham’s 2021 Netflix special Inside, obviously, only one word different from the Pixar film Inside Out. Burnham released Inside at age 29. He obviously exhibited and commented on the social anxiety both created and perpetuated by the pandemic. I cannot image how it affected the social development of a 9-year-old girl if it affected fully grown adults as much as it did to Burnham.

Armond White’s Review

I will now transition to Armond White’s review of Inside Out 2 in National Review. White might be the most idiosyncratic movie critic in the post-Ebert online age. He will lambast universally acclaimed films, such as Get Out, while he exalts Adam Sandler’s cinematic train wreck Jack and Jill from 2011. Nowadays, the contrarian, conservative critic will almost always tie everything back to the political cleavages of the day from a right-wing reactionary lens, but he will also make points that nobody else wants to say. Despite his transparent political biases, he still has knowledge of cinema in a way devoid in fellow right-wing cultural commentator Ben Shapiro, who will basically lambast everything that came out of Hollywood since The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King won Best Picture at the Academy Awards in 2003.

With Inside Out 2, Armond White had to tie it back to Donald Trump and the pandemic, but I still found his critique meaningful since he considered the 2015 film Inside Out as perhaps the best Pixar film of all time. He obviously had some affection for the narrative of Riley. In other words, I still found poignancy in what he said after sifting through some of the predictable, robotic right-wing talking points.

Unlike the first film, White gave a poor review of Inside Out 2. In White’s review, he states:

Inside Out 2’s Freudianism allows Pixar addicts to indulge both neurosis and psychosis — entertaining the psychological detachment from reality that gave way to Trump Derangement Syndrome and that causes post-Covid susceptibility to government and media tyranny. That’s the essence of Riley’s newly added characteristics: Anxiety (orange) says of Riley, “My job is to protect her from the scary stuff she can’t see. I plan for the future.” It’s a funny line but disguises adult self-justification behind childhood innocence.

Such is the Millennial psychological condition that Inside Out 2 refuses to examine. It avoids the irrationality brought about by TDS and the Covid lockdowns. No wonder oversized Embarrassment (voiced by Paul Walter Hauser, who memorably played Clint Eastwood’s Deep State victim in Richard Jewell) resembles the big red, furry, black-fanged, tennis-shoed, tooth-shaped monster Gossamer of the Looney Tunes classics.

Inside Out 2 is another example of gaslighting. It is a Millennial version of Isaac Asimov’s Fantastic Voyage (inside the body, now inside the mind). The clarity of mixed emotions was fascinating in the first film, but the comic negativity here, using Fear, Anger, Disgust, and Sadness to create Riley’s Sense of Self and Joy to shape her “belief system,” is just plain narcissism. Psychology has changed since TDS, and its moral loss is felt in this non-spiritual, agnostic cartoon.

I do agree with some sentiments that White articulates here. Specifically, I agree that psychology has changed since the rise of Trump and COVID-19. By extension, the experiences of puberty and childhood have changed although we cannot make fully-fleshed assertions about this potential societal trend until the younger zoomers and older Gen Alpha children become older.

He makes a decent point with the introduction of Anxiety, a word tossed around so much during the pandemic. Unlike the original five emotions (Joy, Anger, Fear, Disgust, and Sadness), Pixar is introducing a literal DSM diagnosis. White argues that we cannot extricate Riley from the experience of the pandemic. This is probably true, but we do not want Pixar pontificating on the effects of the pandemic and doing a sociopolitical critique of that nature through the lens of a 13-year-old girl, who likely would have no political views or knowledge of her own.

However, I find my greatest interest with his mentioning of millennials. Sure, Riley is 13 years old, but she was created by millennial animators (and older zoomers) and writers in California somewhere. Writing for a character not your age can be difficult but, especially, in this circumstance. As I have already said, I think that the difference between a girl born in 2004 and a girl born in 2011 is massive. I cannot imagine that a 28-year-old USC graduate can perfectly envision the experience of a 13-year-old girl.

Despite this cultural chasm, coming-of-age and puberty are universal themes, so what comes off as inaccurate in Inside Out 2 with the portrayal of 13-year-old Riley? The first film anthropomorphized emotions that every human has. The writers and animators relished in this fact during the scenes that they enter the brains of Riley’s mother and father and see that they have the exact same emotions as her.

More specifically, Riley and her father have differences in both age and gender, but they experience anger and sadness and joy in similar ways because they are human. The sequel introduces emotions that I cannot imagine the father believably having. I do remember seeing an Anxiety analog with Riley’s father. We could probably believably envision Embarrassment too, but can we imagine Ennui? That character appears on her smartphone the entire movie. How many kids know what ennui is? It’s not necessarily a “universal” emotion like sadness or joy.

Beyond just Anxiety — a buzzword in our psychiatry-obsessed zeitgeist — Ennui more so embodies the millennial ethos of the film with the obsession with her smartphone. My issue with these additional emotions even more so came from the fact that I couldn’t keep track of all of them. The only one that stood out to me was Maya Hawke’s Anxiety, but we now had nine emotions instead of five. Having nine emotions dilutes the importance of each one. We could have probably just gotten by with Anxiety and eschewed the very few words that Paul Walter Hauser uttered near the end of the movie.

Conclusion:

Effectively, to expound on White’s sentiments, Inside Out 2 can become projection for neurotic Hollywood writers. No, this film did not veer into the absurdity of casting Woody Allen as a neurotic ant in 1998’s Antz, which opens with a scene of Allen’s character in ant therapy. It might as well be Annie Hall, but no child in 1998 could relate to the 1970s neuroses of Woody Allen. I can vividly imagine Jeffrey Katzenberg cackling somewhere in Los Angeles at the idea of Woody Allen voicing an ant in psychotherapy although that appeal is very narrow, especially, for a children’s movie.

Again, Inside Out 2 avoids this degree of cross-generational, anachronistic projection — but it comes close. Nonetheless, I really liked Inside Out 2. I might say that I even loved it with a month and a half passing since I saw it. The film’s great qualities far outweigh any millennial/zoomer neuroses in the film or any other weaknesses that I articulated.

I think that Inside Out 2 is my favorite Pixar movie since Toy Story 3 in 2010. That’s a strong statement, but it’s true. It improves upon the original and analyzes new thematic elements. It deserves to be Pixar’s highest-grossing film ever. This film taught me to love the idea of the sequel and reminded me that sequels can go beyond cynical cash grabs. Sure, Disney grabbed a lot of cash in the process, but I guess it’s a win-win in that case.

I can’t wait for 2033 when we see Inside Out 3 and Riley starts taking Prozac, Xanax, and Adderall in her freshman year of college. How will her emotions respond to psychotropic drugs? Maybe Eli Lilly can sponsor it, but — until then — Pixar has satiated me and successfully grabbed my dollars.