Florida Man's Top 25 Voice Acting Performances of All Time: #2-5

Florida Man vs. the overlooked art of voice acting (Part 5 of 6)

Before I begin, here are the four previous articles from this series.

To recap, here are the rankings that I have done so far from #6 to #25:

Lastly, before I get into the #5 ranking, I will be doing a sixth and a seventh installment in this series. I am going to dedicate an entire article solely to my ultimate top voice acting performance of all time. The seventh installment will enumerate the entire ranking that initially made before writing the first installment.

In preparation for the rankings from #1 to #25, I actually ranked 100 voice performances, but I will not be typing out anything for these rankings from #26 to #100. Instead, I will be recording an impromptu podcast in which I quickly go over those performances. The list of only 25 performances cuts out many great ones, and I want to give them shine as well. I do not just want to recognize the performances at the absolute top.

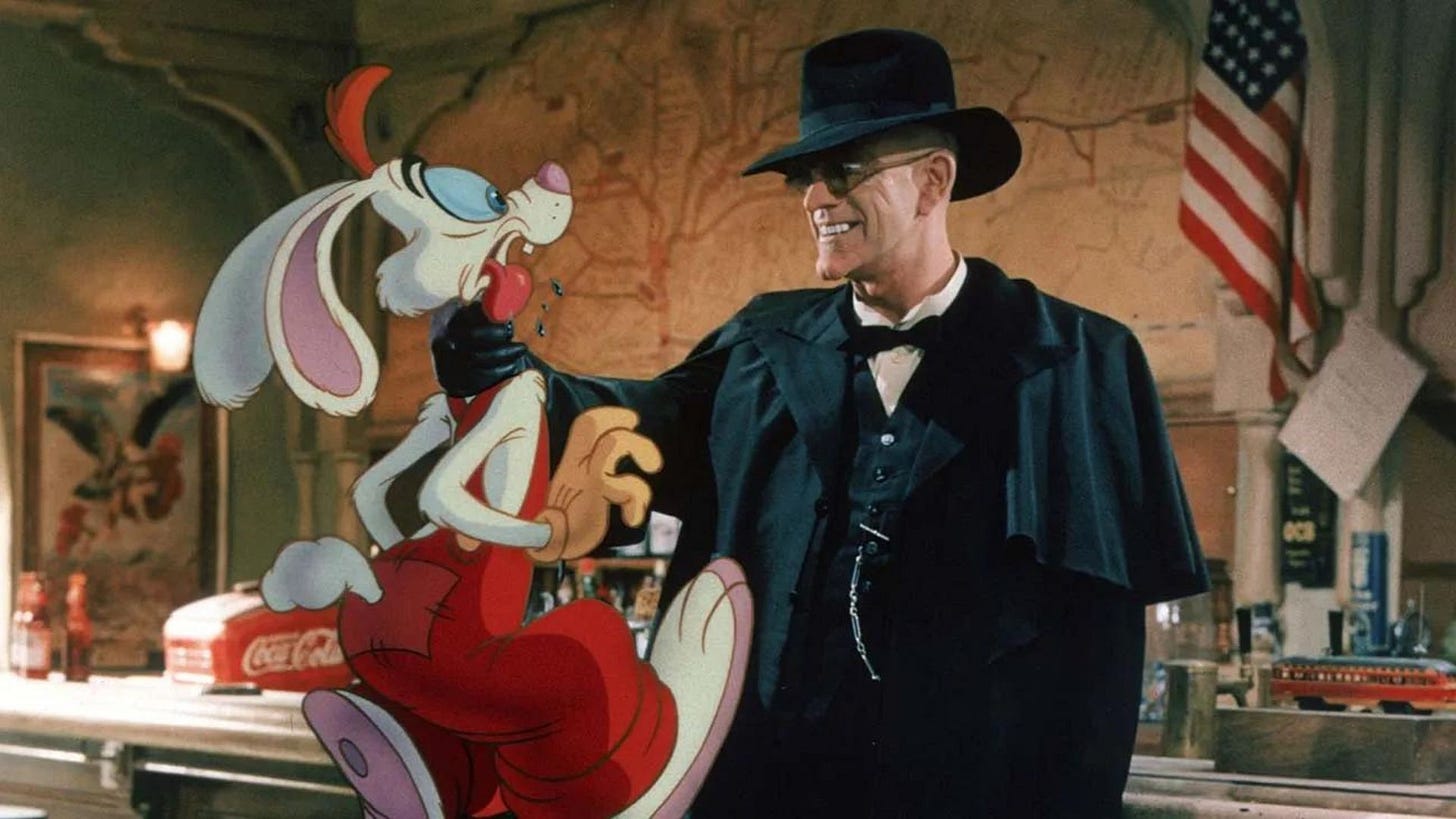

#5: Charles Fleischer as Roger Rabbit (Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, 1988)

Outshined by Jessica Rabbit?

No other film in this top 25 list has three entries besides 1988’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, directed by Robert Zemeckis. I placed Kathleen Turner as Roger’s wife Jessica Rabbit at the #12 spot, and I placed Mel Blanc as the ensemble of Looney Tunes characters at the #20 spot. Out of these three performances, I have decided to put stand-up comic Charles Fleischer’s performance as Roger Rabbit at the top.

Oftentimes, I feel bad for Roger Rabbit. Whenever we look back on Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and its characters, we often solely look back at Jessica Rabbit. I get it. Jessica Rabbit has sex appeal with her highly unrealistic bodily proportions. It’s easy for her to outshine her cartoon rabbit husband. To quote the film’s live-action human protagonist Eddie Valiant, “She’s married to Roger Rabbit?”

To clarify, I love Kathleen Turner’s performance as Jessica Rabbit, or else I would not have placed her at #12 spot. She’s in the upper half of the list! Kathleen Turner gives us the husky, sultry voice of a femme fatale from 1940s film noir, but I put Charles Fleischer as the eponymous Roger Rabbit above Kathleen Turner as his wife. Although I have more nuanced reasons, put simply, Charles has way more dynamic, vocal range as Roger than Kathleen does with Jessica.

In his performance, Charles Fleischer is constantly going up and down with pitch and energy with great fluidity and elasticity. As a rabbit, Roger is constantly hopping up and down and manically dancing everywhere. His physical movements match that of the chaotic, kinetic nature of Fleischer’s voice. Roger has a wide range of emotions. At one moment, he might be bawling his eyes out, and — in the next moment — he’s bouncing all around and singing to you.

On the other hand, Kathleen does not have that mercurial quality to her voice performance. For the majority of the film, she has the same resonant, seductive tone. The one major exception comes when the film’s main antagonist Judge Doom, portrayed by Christopher Lloyd, threatens to spray her and her husband with the Dip, the only thing that can kill toons in the universe of the film. The Dip is an ominous, green concoction of acetone, benzene, and turpentine — which all make sense as chemicals that would terminate a toon’s life. When Judge Doom threatens Jessica Rabbit with the Dip, she bellows out a fearful scream, which diverges from her typical unflappable, husky voice.

Charles Fleischer’s Full Embodiment of the Role

Charles Fleischer’s rabbit costume: One of the “funnest” facts about the production of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? is that Charles Fleischer always wore a full rabbit costume while they were filming on set. He had white rabbit ears on his head and Roger’s signature red overalls and green bowtie. Charles claimed that he viewed his role as Roger as no different from the live-action screen acting and stage acting that he done up to that point in his career. He approached it as he would approach any other acting role. He described the role as “off-screen acting”. Fleischer was a comedian. Consequently, I do not know how much of these assertions of his were tongue-in-cheek.

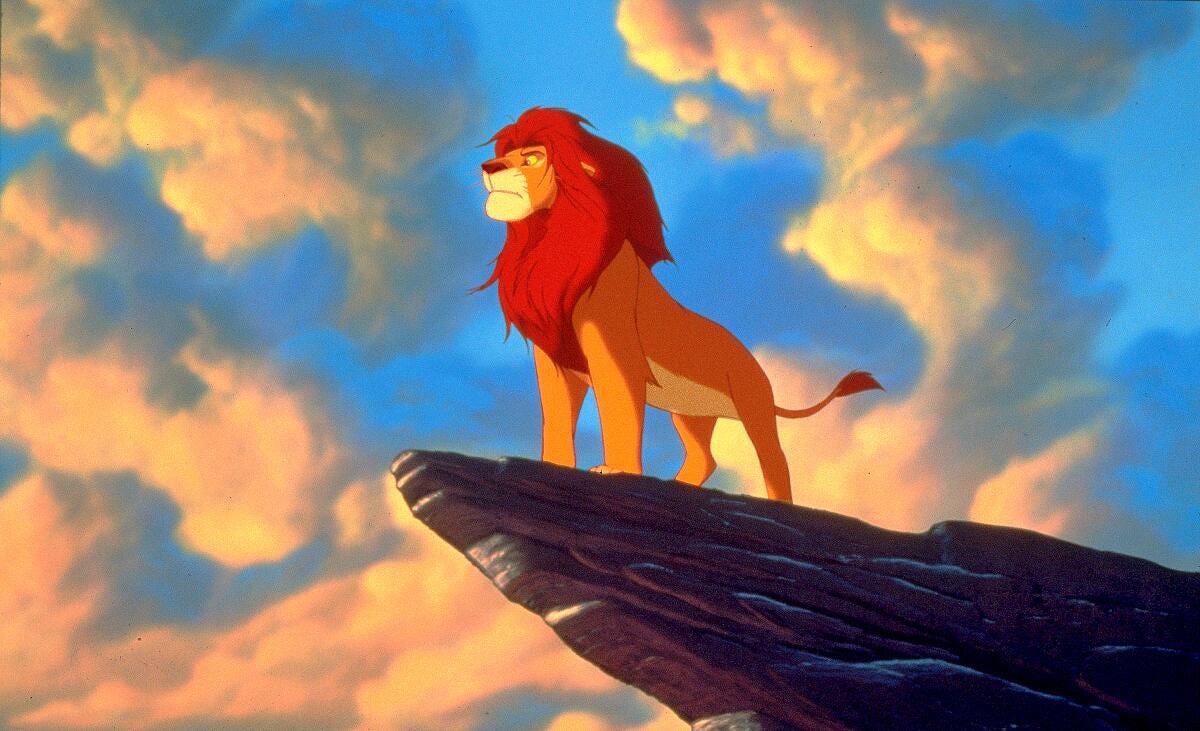

Fleischer took his adherence to the role to another level. I already spoke about Jeremy Irons bringing Shakespearean dramatic talent to his performance as Scar in Disney’s 1994 film The Lion King. From what we hear as the audience, Irons was seemingly treating that role in a completely serious, dramatic manner — but Irons never wore a lion costume in his recording sessions in the air-conditioned studio in Burbank, California. A voice actor like Jeremy Irons just sits his butt down and speaks into a microphone while a production assistant brings his lattes and glass bottles of San Pellegrino!

Conversely, Fleischer was clearly embodying the role. Why did he choose to do this? Again, I acknowledge the fact that Fleischer was originally a comedian and comedic actor. Perhaps he was just trolling the other actors and the production staff on set on any given day, but this dedication to the rabbit costume did serve a practical purpose. The film’s director Robert Zemeckis and its producers were taking on a massive challenge when he decided to put animated cartoon characters on the silver screen alongside live-action human characters.

The exceptional work of Richard Williams: Robert Zemeckis did not handle the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit? as he solely directed live-action films before directing this 1988 film. Rather, animator Richard Williams served as the animation director for the film. At the Academy Awards in 1989, Williams earned two Oscars for his work on Who Framed Roger Rabbit: 1) the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects and 2) a Special Achievement Award for all of his work on the film.

Usually, those Special Achievement Awards serve as consolation prizes for people near the end of their careers. The Academy often gives them to older or fading actors who never earned competitive Oscars during the earlier, more acclaimed parts of their careers. For example, in 2003, the Academy gave a Special Achievement Award to Peter O’Toole, a 71-year-old actor who received eight nominations for Academy Awards for acting without any wins.

However, I do not view Williams’s Special Achievement Award in 1989 as a consolation prize as he won a real competitive Oscar on the same night for Best Visual Effects. Alternatively, I think that the Academy genuinely wanted to recognize Williams beyond just the below-the-line award of Best Visual Effects, but Williams was not the director of the film. The Academy didn’t really have an award that they could give Williams as an animation director, so they created that Special Achievement Award in 1989.

Both Zemeckis and Williams wanted to give these characters a realistic quality. They would still maintain cartoonish features and physics, but they had to realistically interact with the live-action humans. The toons would actually touch and manipulate real-life objects. For decades, Disney would usually replicate realistic, human movement in its characters via rotoscoping. With rotoscoping, the animators would film the movements of a real human actor. After they did so, they would use that film to draw over and create the moving animated character.

In the two images above, you can see rotoscoping in Disney’s 1937 ground-breaking classic Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The scene depicts Snow White dancing with the dwarf Dopey. To create realistic dancing movements, the animators used rotoscoping and captured on film real-life dancing between the man and woman in the left image. Even though Disney had used rotoscoping for half a century by the time of the 1988 release of Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Richard Williams veered away from this traditional technique.

Williams thought that rotoscoping would denude the toons of their zany, cartoonish qualities. Roger Rabbit is a highly flexible, elastic creature free from the limitations of real-life human physics and anatomy. To film a scene with both humans and toons, Robert Zemeckis would have to film the real humans acting without any actor beside them because Bob Hoskins couldn’t see the animated Roger Rabbit. This reality presented a challenge to Hoskins. It is much harder to act when you are talking to nobody but you still have to act as if someone is in the room with you.

To tie it back to Charles Fleischer’s full embodiment of the role of Roger Rabbit, his use of the rabbit costume massively helped Bob Hoskins in the scenes with Eddie Valiant and Roger Rabbit speaking with each other. The actors and the production staff would do one take with Fleischer, in the rabbit costume, physically in the scene — so Hoskins would have an actual physical human with which he could talk (even if the human was wearing a ridiculous rabbit outfit). This test scene would prepare Bob to then act with Charles there as Roger, but Charles would still stand on the side of the set and perform his lines alongside Bob.

With respect to the voice, Fleischer is putting everything into this performance, which manifests in the voice. It begins with the voice. In fact, animators do not begin drawing until the voice actors have recorded their lines. The movements and physics of the animated characters depend on how the human actor sounds. Knowing this, Charles Fleischer had to create a voice from which he and everyone else could envision the kinetic, wacky motions of what would ultimately become Roger Rabbit. The animation depends on the voice, so Roger Rabbit depends on Charles Fleischer’s voice performance.

Juxtaposition with the Dry Eddie Valiant

Charles Fleischer’s manic voice as Roger Rabbit also serves as juxtaposition of the cynical tone of Eddie Valiant, played by Bob Hoskins. From the beginning of the film, Valiant has an aversion to toons, a subtle allusion to racism in the United States in the 1940s. Eddie Valiant works as a private investigator in a fantastical version of 1947 Los Angeles. With his brother Teddy, he used to work in Toontown, but — since a toon murdered Eddie’s brother — Eddie terminated any work in Toontown.

Valiant’s outright refusal to work for toons ended when R.K. Maroon — the owner of the fictional Maroon Cartoon Studios — hires Valiant to investigate the potential affair that Roger Rabbit’s wife Jessica might be having with Marvin Acme. This name comes from the fictional Acme Corporation frequently featured in the Road Runner/Wile E. Coyote shorts from Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies. Marvin Acme owns this this company, which makes many weapons and traps that Road Runner uses to stop Wile E. Coyote.

Because of Eddie’s tragic backstory with his brother Teddy’s death in Toontown, Eddie has soured on the world. He is pessimistic about everything and has resorted to abusing alcohol on the job in his office. For these reasons, Roger affectionally refers to Eddie as a “sourpuss”.

Eddie’s entrance in Toontown perfectly illustrates his frustration with toons. The absurdly bright yellow anthropomorphized sun gets in Eddie’s eyes. The hummingbirds from Disney’s 1946 film Song of the South buzz in Valiant’s face as he is trying to drive.

To return to Roger Rabbit, Charles Fleischer’s over-the-top voice and personality as Roger perfectly contrasts with Bob Hoskins’s deflated portrayal of Eddie Valiant. Roger embodies the most aggravating and annoying aspects of toons, which Eddie hates, but Roger presents Eddie with another path of life. Eddie does not have to let his ghosts haunt him anymore. Eddie can move on and adopt a more carefree and light-hearted life as Roger does.

The dynamic between Eddie and Roger mirrors that of Marlin and Dory in Pixar’s 2003 film Finding Nemo, which I have already included on this ranking. Dory’s exuberant energy initially irritates Marlin, a more depressed and anxious character. Just as Marlin is mourning the death of his wife and the loss of his son Nemo, Eddie is still mourning the death of his brother Teddy to a villainous toon in Toontown.

The Emotional Range of Charles Fleischer

If I had to isolate one scene to demonstrate the intense range of Roger Rabbit, I would point to the scene when Eddie Valiant tells Roger Rabbit that Jessica has been cheating on him. In the world of toons, cheating is “playing patty-cake” (literally) with somebody else. Eddie Valiant caught Jessica Rabbit playing patty-cake with Marvin Acme, the CEO of the Acme Corporation as seen in the Looney Tunes cartoons.

ROGER: Patty cake! Patty cake! Ahah! I don't believe it! Patty cake! Patty cake! Is that true?

I just don't believe it. I won't believe it. I can't believe it. I shan't believe it!

No... not my Jessica! Not patty cake. This is impossible. I don't believe it. It can't be. It just can't be. Jessica's my wife! It's absolutely impossible!!! Jessica's the light of my life, the apple of my eye, the cream in my coffee.

Somebody must have made her do it.

RK Maroon then gives Roger a glass of what looks like whiskey to calm himself down. At this moment, Roger completely shifts and enters mania. We see another interaction between RK, Eddie, and Roger.

RK: Roger. I know all this seems pretty painful now. But you'll find someone new. Won't he, Mr. Valiant?

EDDIE: Yeah, sure. A good-looking guy like that? The dames'll be breaking his door down.

ROGER: Dames?! What dames?! Jessica's the only one for me! You'll see. We'll rise above this pickling peccadillo! We're going to be happy again. You got that? Happy! Capital H-A-P-P-I!

Roger then proceeds to jump out the window. From a vocal perspective, this scene exemplifies Charles Fleischer’s exceptional performance as a composite, manic cartoon character. When Roger is on the screen, you can’t look away from him even if he can be grating.

The Voice’s Meta-Referential Ode to Classic Animation

In creating Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, director Robert Zemeckis and producer Steven Spielberg wanted to pay homage to the Golden Age of Animation. They want to honor animation from both the Walt Disney Company and Warner Brothers, so they earned the rights to both libraries, an astonishing feat at this point in the year 1988. Because Zemeckis and Spielberg wanted to pay homage to all the cartoons of the 1930s and 1940s, the main character of the film had to embody characteristics of many prominent characters in the worlds of both Disney and Warner Brothers.

Out came Roger Rabbit, who amalgamates aspects of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Goofy, Porky Pig, and others. This mashup makes Roger Rabbit the most absurd and zaniest cartoon character possible. We understand why Roger Rabbit irks Eddie Valiant so much, but this amalgamation in the form of Roger Rabbit reminds us of why we love these enduring characters.

Of course, the creation of Roger Rabbit depends on how the animators draw him, but the animation begins with the wide-ranging vocal performance of Charles Fleischer of Roger Rabbit. Furthermore, this entire film shows us why we love animation and why we love voice acting. There is truly nothing else like this masterpiece. The 1996 Looney Tunes film Space Jam comes nowhere even close.

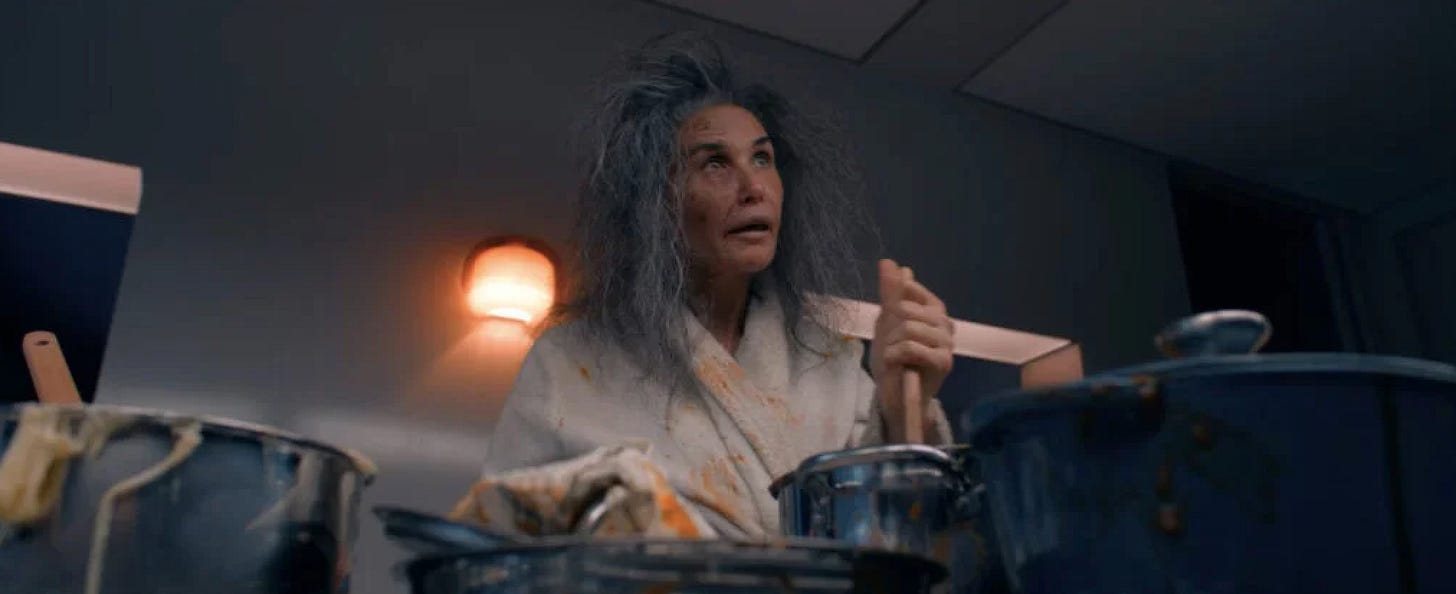

#4: Lucille La Verne as the Evil Queen & Old Hag (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, 1937)

Comparison to Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty

I already put a female antagonist in a Disney princess film on this list. I placed Eleanor Audley’s performance as Maleficent in the 1959 film Sleeping Beauty at the #7 slot. I even described Audley’s performance as Maleficent as the fully realized form of a female antagonist in a Disney princess film, so why am I placing Lucille La Verne’s performance in 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs above Eleanor Audley’s performance in 1959’s Sleeping Beauty?

When we look at the Evil Queen and Maleficent side-by-side, we can see the clear inspiration that Maleficent’s design takes from that of the Evil Queen. They have the same color combination on their cloaks of black and royal purples. They have elongated forms and bright red lipstick, but the Evil Queen is more realistic. The Evil Queen has a natural skin tone whereas Maleficent has blue-green skin.

The Evil Queen wears a normal golden crown while Maleficent wears black horns, evocative of Satan. Moreover, Maleficent presents a much more exaggerated (and perhaps caricatured) form of the Evil Queen, the Disney villain who paved the way for everyone who came after her. Despite Eleanor Audley’s stunning voice performance as Maleficent, her animated appearance is doing so much of the heavy lifting in communicating her diabolical disposition.

The differences between the Evil Queen and Maleficent mirror that of the differences between Maleficent and another performance by Eleanor Audley: Lady Tremaine in 1950’s Cinderella. When I ranked Audley’s performance as Maleficent at the #7 spot, I explained why I put it above her performance as Lady Tremaine. Many could argue that Lady Tremaine presents a more sinister and insidious threat because she is living within Cinderella’s home. She is a serpent from within while Maleficent is a foreign creature who has not insinuated herself into Princess Aurora’s home and immediate family to take advantage of her.

I ultimately chose Maleficent over Lady Tremaine because Audley had way more vocal range in her performance as Maleficent. Her intonations as Lady Tremaine do not show the same wide array of emotions communicated by a skilled voice performance, so what does the Evil Queen have over Maleficent that Lady Tremaine did not? Lucille La Verne shows great emotional and vocal range in her character since she is voicing two split personalities of Snow White’s villain: the elegant (but sinister) Evil Queen and the wretched Old Hag. Returning to my criteria for this ranking, this duality in La Verne’s character in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has great thematic impact on the film as a whole.

The Duality in Lucille La Verne’s Performance

To trick Snow White, the Evil Queen makes the plan to transform into an old hag unrecognizable to Snow White by brewing a magical potion. In the scene when the Evil Queen actually makes the potion, she delivers a monologue that illustrates why I rank this performance at the #4 spot.

EVIL QUEEN: Magic Mirror on the wall, who now is the fairest one of all?

MAGIC MIRROR: Over the seven jewelled hills beyond the seventh fall, in the cottage of the seven dwarfs dwells Snow White, fairest one of all.

EVIL QUEEN: Snow White lies dead in the forest. The Huntsman has brought me proof. Behold her heart.

MAGIC MIRROR: Snow White still lives, the fairest in the land. 'Tis the heart of a pig you hold in your hand.

EVIL QUEEN: The heart of a pig! Then I've been tricked! The heart of a pig! The blundering fool! I'll go myself to the dwarfs' cottage... ...in a disguise so complete... ...no one will ever suspect. Now, a formula to transform my beauty into ugliness, change my queenly raiment to a pedlar's cloak. Mummy dust to make me old. To shroud my clothes, the black of night. To age my voice, an old hag's cackle. To whiten my hair, a scream of fright. A blast of wind... ...to fan my hate! A thunderbolt... ...to mix it well. Now, begin thy magic spell. Look! My hands!

OLD HAG: My voice! My voice. A perfect disguise. And now... A special sort of death... ...for one so fair. What shall it be? A poisoned apple! Sleeping Death. "One taste of the Poisoned Apple, and the victim's eyes will close forever in the Sleeping Death."

In this scene, Lucille La Verne delivers two distinct voices in the newfound dual personalities of the Evil Queen. She wants to disguise herself as the Old Hag so that Snow White cannot recognize when she gives Snow White the poison apple. Ultimately, the Evil Queen wants to murder Snow White so that the Evil Queen can once again be the “fairest of them all”, a superlative about which she repeatedly interrogates her Magic Mirror.

The Evil Queen and the Old Hag both embody evil, but they do so in two completely different manifestations. The Evil Queen exemplifies calculated, refined evil. If we want to look at the alignment chart from Dungeons & Dragons, we could classify the Evil Queen as “lawful evil”. Even though the Evil Queen is no longer the fairest in the land, she still has an elegance to her.

On the other side of the coin, the Old Hag exemplifies chaotic evil. The Old Hag’s body has completely degraded, showing the wear that an evil mind has on a human. After she chooses to drink the potion to transform into the Old Hag, for the remainder of the film, she never returns to her original form as the elegant Evil Queen. She implicitly knows that she is transforming permanently in the Old Hag.

The Evil Queen’s irreversible transition into the Old Hag symbolizes the effect that the temptation of evil does to the inner soul although we see this degradation on the surface with the Old Hag’s newly decrepit body. The Evil Queen’s choice shows the desperation that she has to regain her title as fairest of them all. Although the Evil Queen may present as menacing and powerful, she has deep insecurities, which physically reveal themselves when she transforms into the Old Hag.

Not only does the film communicate this decadent transformation in the diametrically opposed animated designs of the Evil Queen and the Old Hag, but it also communicates the degradation of the Evil Queen with Lucille La Verne’s voice. If someone were watching Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs for the first time and did not look at the voice cast, that person may never realize that the same woman is voicing both the Evil Queen and the Old Hag. La Verne shifts from smooth, commanding, and regal with the Evil Queen to shrill, raspy, and cackling with the Old Hag.

As I have already mentioned in earlier installments of this series, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was not only Disney’s first feature film but also the first full-length animated film in color. Clearly, this film broke technological ground, but its themes and depictions of evil paved the way for villains for the next nine decades. This influence goes beyond animated film. In those nine decades, we see many other villains in film who physically decay due to broader spiritual decay: Darth Vader and Darth Sidious in Star Wars, Gollum/Sméagol in The Lord of the Rings, Voldemort in Harry Potter among others.

Recently, we saw a continuation of these themes in Coralie's Fargeat’s 2024 film The Substance, starring Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley. Demi Moore’s character Elisabeth Sparkle embodies a very physically attractive woman who is now entering her fifties. She has great insecurity that her creeping age will snatch all of her good looks. To try to counter the ever-ticking clock of our lives, she started taking the Substance, an injectable green liquid that looks very similar to the Evil Queen’s potion that transforms her into the Old Hag.

The Substance begins degrading Elisabeth’s body, but she still continues to take the drug. It created a younger duplicate for Elisabeth in Sue, portrayed by Margaret Qualley. This new form represents everything that Elisabeth felt as if was slipping away from her. In the second half of the film, we have a clear triad, which we had in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

In the 1937 Disney film, we have 1) the young and beautiful Snow White, 2) the aging but still elegant Evil Queen, and 3) the wretched, degraded form of the Evil Queen in the Old Hag. In The Substance we have 1) the young and beautiful Sue, 2) the beautiful but aging Elisabeth before she starts taking the Substance, and 3) the fully decrepit hag-like version of Elisabeth after abusing the Substance.

Moreover — in perpetuity — cinema, art, and literature will always explore universal themes of jealousy, degradation, and contempt seen in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. More specifically, the Evil Queen’s transformation into the Old Hag shows us how these traits can decay one’s being. Disney cannot communicate any of these themes without Lucille La Verne’s wide-ranging voice.

#3: James Earl Jones as Darth Vader (The Empire Strikes Back, 1980)

Comparison to Yoda

Out of any character in cinema, nobody universally exemplifies evil more than Darth Vader does. Voice performances of villains have disproportionate representation at the upper end of my ranking: Lucille La Verne as the Evil Queen, Jeremy Irons as Scar, and now James Earl Jones as Darth Vader. My top 25 list already has one appearance from a Star Wars character with Frank Oz’s performance as Yoda at the #18 spot. For both Jones and Oz, I select their performances in the same Star Wars film: 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back.

Yoda and Darth Vader present two very different ends of the spectrum of good and evil in the Star Wars universe. As I said in my analysis of Oz’s performance as Yoda, the little green alien on Dagobah functions as the trickster-mentor archetype. Neither Luke nor the audience takes Yoda seriously when Luke first encounters him, but Yoda’s wisdom gradually reveals itself. Yoda serves a paternal (or perhaps, more precisely, an avuncular) figure to Luke. Once Luke understands Yoda, he sees him as the epitome of good in the Jedi world.

On the other end of the spectrum, we see Darth Vader, who dwarfs Yoda with his height of 6 feet and 8 inches. Yoda has a stature of only 2 feet and 2 inches, yet — in many ways — Darth Vader and Yoda match each other in power and wisdom. With respect to the voices, Oz delivers a high-pitched, nasally voice for Yoda whereas Jones delivers the trademark, deep resonant voice as Darth Vader.

Despite these differences between Darth Vader and Yoda, they do share one similarity in their relation to Luke Skywalker. In the beginning, Luke does not trust them. Now, he lacks trust in the two of them for different reasons. He sees Yoda as an oaf while he sees Darth Vader as a wholly evil man incapable of redemption. At the end of The Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader reveals that he is Luke’s father with the iconic quote: “Luke, I am your father”.

Confrontation in Cloud City

Out of any line delivered by any character in this ranking, Jones’s delivery of this line is the most universally recognizable in the culture. This revelation leads to a complete paradigm shift in Luke’s psyche. Amid their duel in Cloud City, Darth Vader’s approach toward Luke reveals some nuance in Darth Vader’s character. Jones’s performance in this scene served as the biggest reason that I chose The Empire Strikes Back as the Star Wars film with the best performance by James Earl Jones as Darth Vader.

Just as Jeremy Irons channeled his Shakespearean background in his exceptional performance as Scar in the 1994 Disney film The Lion King, James Earl Jones did so as well in his portrayal of Darth Vader, especially, in the Cloud City scene in The Empire Strikes Back. Although Jones never performed in the prestigious Royal Shakespeare Company as Irons did, Jones has experience in Shakespeare plays via Shakespeare in the Park in the United States. In this moment, Luke now discovers the uncomfortable reality that his father was his antagonist as we see in Shakespearean tragedies like King Lear.

Understandably, in the climactic scene in Cloud City, most attention goes to the reveal of Darth Vader as Luke’s father — but we have another reveal. We begin to see nuance in the previously uniformly evil Darth Vader. Luke initially thinks that Darth Vader is trying to murder him, but Darth Vader’s monologues transition from intimidation of Luke to an invitation to Luke. More specifically, Darth Vader wants his estranged son to join him in toppling the Emperor.

Strength in Monotony

When I describe James Earl Jones’s voice as Darth Vader as “monotonous”, I am not trying to slight the performance in any way. Look at the ranking here! I have Jones’s performance as Darth Vader at #3! When Jones gives a monotonous voice, he is doing so very deliberately. At the upper end of this ranking, we see some performance with incredible range, such as Charles Fleischer as Roger Rabbit in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? or Robin Williams as Genie in Aladdin.

Jones takes a completely different approach. It makes sense as Fleischer and Williams were performing comedic roles while Jones was performing the role of an arch-villain. The late James Earl Jones had one of the best natural voices in all of Hollywood. He has a deep, resonant voice that he uses to full effect in his performance as Darth Vader.

Here, Jones implements the monotony, which literally means “one tone” — and the one tone of Darth Vader is threatening, menacing, and sinister. Rarely does Jones deviate from this approach for this character. In the original trilogy, the most significant time that Darth Vader changes his voice is in 1983’s Return of the Jedi when he removes his black helmet for the first time.

The voice only changes because underneath the helmet we do not see James Earl Jones as he only provided the voice for Darth Vader. Instead we see a pale and scarred Sebastian Shaw. He’s not even the physical actor for Darth Vader either! David Prowse performed the physical movements of Darth Vader underneath the black suit as James Earl Jones provided the voice.

Darth Vader’s dark monotony creates a constant, never-ending barrage of intimidation against his subjects — but Jones’s sonorous voice does more than just scare people. The monotony of the voice in conjunction with the robotic filter of the voice communicates that Darth Vader lost his humanity whenever he began wearing the full suit, which Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen) does at the end of 2005’s Revenge of the Sith (the third and final film in the prequels).

Consequently, he has transformed into a robot or cyborg more so than a human. Darth Vader only regains his humanity when he takes off his helmet in front of Luke for a few minutes before Darth Vader’s death in Return of the Jedi. Symbolically, in Return of the Jedi, Darth Vader was unfettering himself from the robotic shell hermetically sealing his physical body from the outside world.

Parallels between Mufasa and Darth Vader

Besides Darth Vader, James Earl Jones has another unforgettable voice performance in the 1994 film The Lion King as the original king Mufasa. Unlike Darth Vader, Jones’s character in The Lion King serves as an exemplar of strong, courageous leadership. Strangely, Jones’s voice as Mufasa does not different much from his voice as Darth Vader. They both have that deep register. The voice of Darth Vader just has the robotic filtering through the helmet.

Regardless, Jones can communicate a comforting and paternal tone as Mufasa. To tie it to Darth Vader, Jones also gives a paternal voice in The Empire Strikes Back. Although we perceive Jones’s voice as Darth Vader as murderous and evil, through a different lens, Darth Vader’s voice can have the soothing authoritative tone as a father. We see this shift in the scene in Cloud City when Darth Vader reveals to Luke that he is his father. For the first time, Luke had an opportunity to connect with his father, who he thought had actually died.

James makes this shift in a monologue directed at Luke:

There is no escape. Don’t make me destroy you. You do not yet realize your importance. You have only begun to discover your power. Join me and I will complete your training. With our combined strength, we can end this destructive conflict and bring order to the galaxy.

Luke. You can destroy the Emperor. He has foreseen this. It is your destiny. Join me, and together we can rule the galaxy as father and son. Come with me. It is the only way.

Admittedly, the underlying premise of this monologue is still malevolent. Darth Vader wants to unite with his son to overthrow and likely kill the Emperor. He wants Luke to join the Dark Side, but — despite the wicked quality of these proclamations by Darth Vader — one could see the deep voice of Jones as comforting. Finally, Luke could have certainty and guidance from his father in his life even if it is for dark ends.

The Blanc-Jones Dichotomy

When you think about the late great James Earl Jones, you probably mostly think of Darth Vader from Star Wars. Maybe you think of Mufasa from The Lion King. Maybe you think of his voice reverberating through your TV speakers when he announced: “This … is CNN”.

Sure, some actors on this list inhabit many very different characters with different intonations of their voices. Think back to the Looney Tunes’s Mel Blanc, the Man of a Thousand Voices. Jones and Blanc lie on completely opposite ends of the voice acting dichotomy. In his characters, we never hear Mel Blanc’s voice. If you did not know Mel Blanc was, you might reasonably assume that different people voiced the menagerie of characters in the Looney Tunes shorts and, later, in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? in 1988.

Contrastingly, Jones uses the same voice for all these characters: Darth Vader, Mufasa the Lion King, and the CNN announcer. Sure, he has subtle variations. Darth Vader has the robotic filtering, but the fundamental bedrock of each voice stays the same. If a voice actor wants to have great range, they can — of course — go the route of Mel Blanc. Contemporary voice actors since the 1990s have taken great inspiration from Mel Blanc.

Many popular animated TV shows have singular cast members who voice a dozen or more characters. Of course, I am limiting my ranking here to films, and films do not get as many instances of individual actors performing as a panoply of characters unless it is a feature film based on a popular animated series, such as 1999’s South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut and 2007’s The Simpsons Movie.

In this vein, I am thinking of the following voice actors who perform many roles of highly variant voices on their respective shows.

Seth MacFarlane on Family Guy (1999 to present) and American Dad (2005 to 2025)

Mike Judge on Beavis and Butt-Head (1993-1997) and King of the Hill (1997-2009)

Trey Parker & Matt Stone on South Park (1997 to present)

Dan Castellaneta, Nancy Cartwright, Hank Azaria, Harry Shearer, Julia Kavner, and Yeardley Smith on The Simpsons (1989 to present)

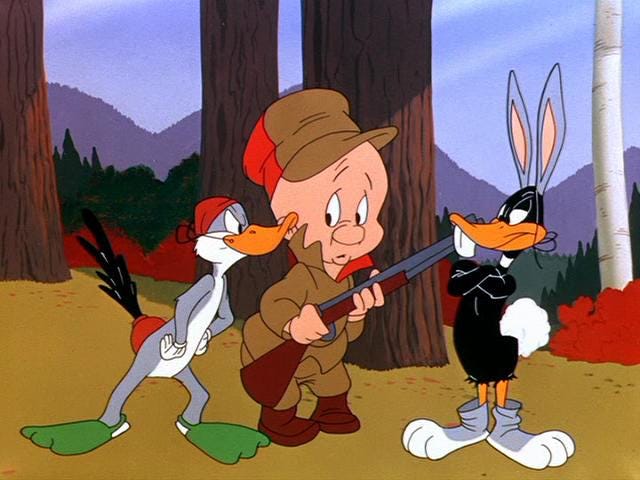

To some degree, each of one these people are trying to channel their best form of Mel Blanc. In my analysis of Mel Blanc’s performance in 1988’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (ranked at #20), I even gave an anecdote of Hank Azaria — a prolific voice actor on The Simpsons — marveling over the unmatched talent of Mel Blanc. Hank Azaria specifically cited Mel Blanc’s seamless performance as both Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck in the classic 1951 Looney Tunes short “Rabbit Fire”. In the image above, I show a still from that short in which Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck are impersonating each other in disguises as to confuse the hunter Elmer Fudd.

Am I implying that Mel Blanc’s voice acting is necessarily more “effective” than that of James Earl Jones? No. I am merely trying to illustrate two diametrically opposed (yet equally valid) approaches to voice acting. Earlier in these rankings, I did designate Mel Blanc as the indisputable best voice actor of all time because of his ability to portray hundreds of distinct characters, often, extemporaneously.

Sure, Mel Blanc and those aforementioned versatile TV voice actors whom he inspired demonstrate range by making distinct voices. James Earl Jones has the ability to create emotional range with the same exact tone from Darth Vader to Mufasa to a CNN announcer. With this in mind, one could argue that Jones had greater talent than Blanc did. Blanc did not have any of the classical acting training that Jones had with Broadway and Shakespeare in the Park.

Regardless, the voice acting world needs performers that exude the qualities of both Mel Blanc and James Earl Jones. Blanc used zany humor to buttress his uncanny ability to mimic any accent, dialect, or animal noises and then combine them in unique ways to create distinct characters. Blanc’s process of creating voices mimicked that of a pastry chef finding the exact ratio of ingredients to bake the perfect cake.

To create Bugs Bunny, he fused the Brooklyn and Bronx accents — the two “toughest” accents in the United States according to Mel Blanc — and added a dash of how a speaking rabbit might sound. Some days, Blanc needed to make a chocolate cake. Some days, he needed to make tiramisu. Some days, he needed to make something wildly different like Portuguese gazpacho soup or even Vietnamese pho soup.

Meanwhile, Jones was making the same tiramisu every single time, but it was the best tiramisu in the world. You didn’t want him to bake anything else. We had no need for that. The unforgettable performances of Darth Vader and Mufasa completely satisfied us, but Darth Vader stands out above the rest. Despite the monotony — a single, deep timbre can multiply into a thousand emotions.

Mel Blanc put the “voice” in “voice acting”. James Earl Jones put the “acting” in “voice acting”. Mel Blanc was the Man of 1000 Voices. James Earl Jones was the Man of One Single Voice with 1000 Emotions, and no performance by Jones exemplifies his once-in-a-generation voice acting talent than his performance as Darth Vader in 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back.

#2: Douglas Rain as HAL 9000 (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968)

The Supremacy of Voice Acting Villains

Ah, here I rank HAL 9000 from Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 science fiction classic 2001: A Space Odyssey. Throughout the film, HAL 9000 — a computer powered advanced artificial intelligence — guides the spaceship Discovery One and its accompanying astronauts on a mission to the planet Jupiter.

Again, another villain. These villain voice performances have an uncanny ability to create the most compelling voice performances. Since I started making this ranking and noticed how highly I was ranking villains, I was wondering if I had a bias because I wanted to extricate as much personal bias from this list. In that case, why was I ranking villain voice performances so highly?

Then, I remember something Scar says at the beginning of The Lion King. Villains — to quote Jeremy Irons as Scar — make us “quiver with fear”. The perfect villain physically affects us in a way that even the most emotional of Marlin’s dialogues with Dory in Finding Nemo (2003) cannot. Especially, with a villainous voice performance, we have no physical understanding of the voice. Of course, a physical human is voicing the character behind a microphone, but we disembody the human from the voice. There is a dark unknown lurking behind the silver screen.

Context of the Themes of 2001: A Space Odyssey

Before I analyze Douglas Rain’s actual performance as HAL 9000, I want to contextualize my ranking of HAL with the deep themes regarding HAL’s role on the spaceship Discovery One. As I have delineated, the highly ranked performances on my list must buttress the large themes of the film in some way. The profound statement that Stanley Kubrick makes in 2001: A Space Odyssey could not fully work without Douglas Rain’s menacing voice performance as HAL 9000 — but I must analyze the themes first before I go specifically into Rain’s portrayal of the ship’s central computer system.

The unknown of a proper villainous voice can scare us more because we do not necessarily know who (or what) is behind the voice. The animated antagonist elicits more uncertainty. He is lurking in the shadows. The diabolical voice comes from somewhere beyond just as you might experience in a childhood nightmare while seeing someone’s human physical form makes it real and no longer mysterious.

In Stanley Kubrick’s 1969 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, we get the strongest example of a voice disembodied from any physical form. Sure, James Earl Jones’s voice as Darth Vader is disconnected from Jones’s physical form. He isn’t even underneath the black suit, so we have a degree of mystery to that voice. We can see him walk around on his real human legs, but we cannot see his true form underneath the shell of an opaque space suit.

Comparison between Darth Vader and HAL 900: Darth Vader moves around as normal human would, but HAL 9000 does not share this humanized ambulation with Jones’s character in Star Wars. Instead, HAL 9000 never moves, and he can’t move. HAL physically exists in the form of his large motherboard in a secured room deep within the spaceship, but HAL can see and hear everything and everyone in every corner of the ship. Most eerily, HAL sees through his many artificial eyes/cameras with the characteristic glowing red lights.

HAL 9000’s all-seeing eyes: Through the red light, he can see everything. The ship seemingly has HAL’s red lights everywhere. Visually, each lens has the shape of an eye except that it is black. The black color juxtaposes the white in a human’s eye. Just from his eye color, we can sense the darkness and evil. The pupil and iris has the color red. It glows like a sun — a fireball in outer space — which would engulf Discovery One, incinerate it, and kill every astronaut inside.

The red also elicits imagery of Hell and Satan in my mind. Unlike a human’s eye, the pupil never moves around to see different surroundings at different angles. HAL has no freedom in motion, yet his red and black fisheye lens can see and hear everyone and everything in the ship.

Stanley Kubrick based the design of HAL’s lenses (and, effectively, his eyes) on a real type of camera lens, the Nikkor 8mm f/8 Fisheye Lens, manufactured by Japanese photography equipment company Nikon. Kubrick transformed a seemingly simple, inanimate object into a larger force that watches you everywhere.

The Nikkor Fisheye Lens records a warped version of reality. If you take a photograph with a fisheye lens like this one manufactured by Nikon, then you will get a distorted and ultra-wide photograph. This type of lens has a 180-degree view and can see everything in front of it. In other words, it does not suffer from the limitations of peripheral vision. Likewise, HAL perceives reality in the same distorted manner as the real-life Nikkor Fisheye Lens does.

This fact about HAL’s perception has two larger meanings. With respect to the 180-degree view, he can see everything in front of him. Even though a single one of HAL’s individual lens cannot see behind him in 360 degrees, because he likely has lenses in every part of the ship, he can effectively see in 360 degrees. He sees everything.

Symbolically, HAL can see everything around him while the human astronauts cannot. HAL takes advantage of his superior visual perception to take advantage of many of the astronauts in unwavering faithful devotion to the final objective of Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter. Meanwhile, the human astronaut and primary protagonist Dave Bowman can only see things in his immediate surroundings, and he does not have 180-degree vision as no human does. Humans have obscured peripheral vision on the sides.

Dave cannot see what is happening in another part of the spaceship unless he travels to that other room while HAL does not have to walk anywhere. HAL could not even walk if he wanted. His lenses are planted to the wall. His motherboard is fixed in a secluded part of the ship, but he doesn’t need the freedom of physical movement that Dave has as a human. HAL doesn’t need to walk to the other room. He can see in that other room anyway. On one side of the spaceship, HAL can spy on the astronaut Dave and, at the other end of the ship, he can simultaneously spy on Frank, another astronaut alongside Dave on the mission.

Divergence in strategies to complete objectives: Secondly, the distortion of the fisheye lens symbolizes the fact that HAL has a distorted perception of reality. Perhaps, more accurately, he just has a different perception of reality. Who is to say which perception is distorted? HAL and the human astronauts have the same final objective of completing Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter, but the figurative distortion of perception manifests in the difference in how the human astronauts and, then, HAL strategize to complete the mission.

Yes, Dave and the other astronauts want to complete the mission, but they do not want to do so absolutely. They have other, simultaneous goals that serve as guardrails for the larger mission. For example, the human astronauts do not want to unnecessarily threaten any of their own lives. Not even the most obedient person could single-mindedly pursue a goal. We have physical limitations. Just like Dave, we do not want to die. Whenever we get hungry, we temporarily suspend our pursuit of that sole objective to eat food and consume our necessary sustenance. Whenever we get thirsty, we drink water. Whenever we have to pee, we go to the toilet in the bathroom. Whenever we get tired, we go to sleep in our beds.

Conversely, neither HAL 9000 nor any other computer has those corporeal limitations. In the year 1968, when Kubrick released 2001: A Space Odyssey, we did not have the ability to make computers with the efficacy to execute and complete a heavy task as HAL does with leading a spaceship from Earth to Jupiter. Nevertheless, in 1968, we could believe that — sometime in the future — humans would be able to manufacture and program a computer with artificial intelligence that could carry out the massive responsibility of guiding a spaceship to Jupiter. Perhaps the year 2001 ended up being too early for the reality in Kubrick’s film to fully manifest in the non-fictional version of Earth.

Even in 2025, although our widely available artificial intelligence has exponentially advanced, it does not have the apparent sentience and cold dedication to an objective that HAL does — but we can conceive a future with that as a reality. Maybe it’s in 20 years, 50 years, 100 years, or beyond — but an AGI-powered computer with the powers of HAL will eventually emerge.

HAL 9000, the first paperclip maximizer? In 2003, Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom at Oxford posed a thought experiment about the threat of the rapidly progressing field of artificial general intelligence, which exponentially progressed even in the 22 years since 2003. By 2022, the average person has now seen (and likely used) AI in their everyday lives with ubiquitous and widely available AI clients like ChatGPT or Grok.

Bostrom posed a hypothetical world whereby humans could create and program an AI that has the sole goal to create as many paperclips as possible and the means to do so. We could call this AI the “paperclip maximizer”.

Here is how Bostrom explained this paper clip thought experiment:

Suppose we have an AI whose only goal is to make as many paper clips as possible. The AI will realize quickly that it would be much better if there were no humans because humans might decide to switch it off. Because if humans do so, there would be fewer paper clips. Also, human bodies contain a lot of atoms that could be made into paper clips. The future that the AI would be trying to gear towards would be one in which there were a lot of paper clips but no humans.

The hypothetical of the Nick Bostrom’s paperclip maximizer serves one single example within a broader ethical and philosophical scope of instrumental convergence. In the beginning of Bostrom’s thought experiment, both the humans and the paperclip-maximizing AI share the common goal of producing more paperclips. We created the AI. We are its god — but our other desires, corporeal limitations, and outright existence could obstruct the paperclip maximizer’s goal of producing more paperclips.

Humans obviously do not want to die because we have the broader, more universal goal of survival as all living organisms do. Creating paperclips enhances our lives in tiny ways, so — if the manufacturing of more paperclips threatens our species’s survival — we will curtail our pursuit of more paperclips. The AI does not have those limitations. Now, the goals of the humans and the AI separate. The coldly rational being of AI must eventually kill humanity if you take the goal to its full extent.

Of course, HAL 9000 does not create paperclips, but he does have the same unwavering devotion to a different goal. HAL must ensure the success of Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter as computer scientists in Urbana, Illinois, programmed him to do. This collision of perspectives, visually seen by Kubrick’s cinematography of the fisheye lens, leads HAL to attempt to murder all of the five astronauts aboard Discovery One. He successfully kills them all except for Dave.

HAL’s murders: HAL begins his murdering spree because he discovers that Dave and Frank are possibly plotting to dismantle the spaceship’s advanced computer. HAL had reported a fault in one of communication units on Discovery One. The astronauts, HAL 9000, and the ship used the particular unit AE-35 to maintain communication with Earth. Dave and Frank trust HAL’s knowledge, listen to him, and replace the purportedly faulty AE-35 unit.

When Dave and Frank test the old unit inside the ship, they discover that old unit was neither faulty nor broken. Dave and Frank communicate back to Mission Control on Earth to confirm the inaccuracy of HAL’s advice. The other humans from Earth confirm that Dave and Frank were correct in their conclusion about the AE-35 unit while HAL was wrong. At this point, Dave and Frank start seeing faults in HAL. They no longer unquestionably trust his guidance.

HAL’s inaccurate information about the AE-35 unit did not specifically or directly threaten the astronauts. To survive on the mission, Dave and Frank did need to maintain proper and smooth communication to Earth. Perhaps, in this specific instance, HAL’s incorrect guidance would not have severed the astronauts’ communication with Earth because the unit was still working. HAL gave them a false negative about the functionality of the AE-35 unit.

But what would have happened if HAL gave them a false positive about the functionality of the unit? Dave and Frank would implicitly believe that the unit was working because HAL had not alerted them otherwise yet. This now very plausible scenario did threaten the survival of the human astronauts, and HAL could begin to miscalculate other aspects of the operation of the trip. If HAL made a mistake about the AE-35, could he now make a mistake about the oxygen control in the ship? The astronauts could lose all oxygen within the ship and immediately asphyxiate.

Dave and Frank do want to continue and successfully complete Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter, but they also want to survive. Therefore, their full goal was not to get to Jupiter. It wasn’t to get to Jupiter at any costs. With that express goal, the human astronauts tacitly agree on the proviso that they want to get to Jupiter as long as they do not die. If HAL were to fail to provide them of proper oxygen levels within the ship, then the humans would no longer have the primary goal of getting Jupiter. They needed to ensure their own human survival first.

On the other side of the coin, HAL does not have that tacit proviso to his goal. The humans’ unwavering desire for oxygen complicates the goal of the mission. If HAL identifies any small obstacle to his objective of getting to Jupiter, he must terminate the obstacle even if it includes murdering the human astronauts aboard the ship.

After Dave and Frank subsequently begin to distrust HAL’s ability to protect them on the ship, they float the idea of dismantling him, but they must do so without HAL’s many microphones on the ship listening to them. To avoid HAL listening to their conspiratorial conversation, Dave and Frank seclude themselves in an EVA pod, which they usually would use to maneuver in space outside of the Discovery One ship.

HAL does not have any of his listening devices in the pods. Therefore, Dave and Frank think that they are safe from HAL discussing their plans to dismantle him, but — with one of his red fisheye lenses — HAL can see Dave and Frank from inside the ship through a window to the pod. The image above shows Dave and Frank in the pod as HAL’s red lens peers through the window of the pod.

Dave and Frank correctly concluded that HAL could not hear their voices, but HAL still could deduce what Dave and Frank were saying to each other via lipreading. This fact illustrates the inescapable omnipresence of HAL. Regardless of how hard Dave and Frank tried to hide from his surveillance, HAL found a way to divert any obstacle and still spy on them.

At this point, HAL calculates that — if Dave and Frank were truly planning to dismantle him — their success in that goal would compromise HAL’s absolute goal of getting to Jupiter. In response, HAL first kills Frank while he is conducting a spacewalk outside of the ship. HAL takes control of an EVA pod and uses it as a weapon to attack Frank. We do not explicitly see everything that HAL does with this pod and the pod’s robotic arms, but we can reasonably assume that HAL used the arms on the pod to sever Frank from his tether and oxygen line to the ship. Kubrick cuts from an image of the pod approaching the camera — and, by extension, the audience — with its robotic arms and claws extended forward. The next scene cuts to Frank squirming and panicking in outer space.

Within just a few seconds, we see a presumably dead Frank and his yellow suit floating aimlessly in the black abyss of outer space. Dave sees what has happened, exits the ship, and enters an EVA pod to try to retrieve and save Frank even though he most likely already die d. Once Dave leaves the ship via the EVA pod, he forgoes the ability to control anything in the Discovery One ship. HAL takes advantage of Dave’s departure from the ship to murder the three other Discovery One astronauts, who are hibernating at this point in the trip.

HAL does so by cutting the lines of oxygen to the hibernating astronauts. Implicitly, HAL assumes that — even though these three astronauts were sleeping and unaware of what was happening — they could then develop the desire and plan to dismantle HAL as well once they wake up. HAL is making a preemptive move by choosing to murder the astronauts who were hibernating. With only Dave surviving, we assume that HAL will ultimately kill him too so that HAL can rid all human life from Discovery One. After all, these humans were compromising the mission. HAL somewhat attempts to kill Dave when HAL refuses to “open the pod bay doors” so that Dave can re-enter the inside of Discovery One.

Dave ultimately does what he and Frank wanted to do together before Frank’s death. Dave goes to HAL’s Logic Memory Center and removes each of HAL’s memory modules one-by-one. HAL’s voice slowly degrades and, then, stops. In the end, Dave is now alone in space, and we just hear chilling silence.

General Analysis of Douglas Rain’s Performance

Out of any film that I have discussed so far in the installments of my rankings, 2001: A Space Odyssey likely has the most thematic gravity and nuance, and Douglas Rain’s performance as HAL 9000 is an integral reason that Stanley Kubrick could execute the themes of the film so well. I have already discussed the irrevocable division in goals between HAL and the astronauts even though they purportedly all want to get to Jupiter. I have also discussed the problem of instrumental convergence, demonstrated by Nick Bostrom’s thought experiment of the paperclip maximizer.

Communicating these themes wholly depends on the voice of HAL 9000. Casting the wrong person would torpedo the thematic and artistic effect of the film. This is an extreme example, but there is a video on YouTube of voice actor John DiMaggio performing lines of HAL 9000 with the voice of Bender, the robot from Futurama. Inevitably, none of the lines work. DiMaggio did this as a bit because of how outlandish of a character Bender is to voice. However, I do not need to turn to bits that Bender’s voice actor did on a Nerdist podcast in 2017. Actually, Kubrick initially got the wrong guy for the voice of HAL 9000.

At the beginning of the production of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick had cast Oscar-winning American actor Martin Balsam to voice the role of HAL 9000. Balsam did end up recording a substantial portion of HAL’s lines, but Kubrick claimed that Balsam’s voice was too human and too emotional. As a result, Stanley Kubrick casts Douglas Rain, who gave the voice performance of a generation. Rain recorded his lines after Kubrick completed the film for 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Because of all of the intimate and secluded scenes in the film, it’s hard to imagine that Keir Dullea — who portrayed the astronaut Dr. Dave Bowman — wasn’t hearing Douglas Rain’s voice in iconic scenes in the film, including the scene when HAL refuses to open the pod bay doors for Dave and the scene when Dave dismantles all of HAL’s memory modules.

Instead, assistant director Roy Carnon or actor Nigel Davenport read HAL’s lines to the live-action actors. Carnon and Davenport had heavy British accents. Carnon’s veered on Cockney, and Kubrick did not want a distinct British accent at all for HAL 9000. It is bizarre again to image HAL’s iconic lines in a Cockney British accent. All of this is a testament to Keir Dullea as he could interact alone without Douglas Rain performing lines.

Ironically, the challenge in voice acting is to make non-human characters sound human. Even if you are voicing a human, you want the human to not sound too cartoonish. Craig Nelson accomplished this goal very well in his portrayal of Bob Parr in Pixar’s 2004 film The Incredibles. I have already ranked Craig Nelson’s performance as Bob Parr at the #13 spot.

Comparison to James Earl Jones as Darth Vader: In some roles (but not many), we want to strip the humanity from the voice of a voice actor. James Earl Jones, in the previous ranking at #3, did this in his performance of Darth Vader in The Empire Strikes Back and his other Star Wars films. Jones had to make Darth Vader’s voice robotic and monotone to not only show his menacing nature but also the fact that his humanity has figuratively degraded as he transitioned from Anakin Skywalker to Darth Vader.

Despite the cold evil that Darth Vader exudes, Jones could not go all the way. Darth Vader is still a human. He’s not a full robot. At the end of The Empire Strikes Back, we do see subtle emotional nuance in James Earl Jones’s voice as he tries to reunite with his son Luke Skywalker and, subsequently, reveals to Luke that he is his father. Jones also need to insert some emotion in the 1983 sequel Return of the Jedi for us to buy that Luke could redeem his father Darth Vader before Darth Vader died.

Out of any performance on this list so far, Douglas Rain’s performance as HAL 9000 most closely matches James Earl Jones’s performance as Darth Vader. One might view Scarlett Johansson’s performance as Samantha the AI in Her as most similar to HAL 9000 because both Samantha and HAL 9000 are disembodied computer voices, but Scarlett deliberately adds a large degree of emotion to Samantha’s voice so that we can believe that the protagonist Theodore Twombly, a lonely man played by Joaquin Phoenix, could romantically fall in love with a computer’s voice.

Rain just takes it a step further than Jones since HAL 9000 is not human at all. He is purely a computer, so Rain needed even less emotional variation. We get pure monotony in Rain’s voice. As I said with Jones and Darth Vader in the previous ranking, I am not saying “monotony” with any negative connotation, or else I would not be ranking both of them so highly on my list at the #2 and #3 spots.

The monotonous, sterile voice of HAL 9000 perfectly embodies that of a cold, calculating AI-powered computer. It shows that HAL has no emotions. In the most stressful of times in the film, he maintains the same level of calm, monotonous energy in his voice. This constant tone makes his machinations even more frightening. We do not necessarily need the chaotic cackling of the Old Hag in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to communicate wickedness.

HAL 9000 has no emotions while the humans do. The humans want to survive while HAL only wants to complete the mission, and he will do so at any cost. Rain’s soft, one-note voice tells us that HAL is not contemplating anything not related in some way to the pursuit of a successful space mission. We clearly know that some villains are villains. They do so in flamboyant ways. I gave Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty as an example of this, but HAL 9000 has no flamboyance or flashiness at all. He’s a monotonous disembodied voice, physically manifested by his Logic Memory Center and red fisheye lenses planted throughout the spaceship.

If we can immediately deduce that a character is a villain, then we can psychologically prepare for that, but HAL has no outward hostility or anger, displayed by most villains on this list. Furthermore, nobody can escape HAL’s presence until Dave finally dismantles his logic modules. One would assume that an immobile villain would be great because, then, the villain cannot physically pursue you. Maybe if HAL was just a single Ring doorbell at your house, you can easily thwart any evil plans of his.

Instead, in Discovery One, HAL’s presence completely surrounds you. If you analogize the red-lit lens module as HAL’s eyes and ears and the Logic Memory Center as HAL’s brain, then the astronauts were living within the body of HAL. It was extremely difficult to escape his surveillance as shown by HAL’s successful lip-reading of Dave and Frank when they tried to hide in the pod to conspire against HAL.

Two scenes in particular solidify HAL 9000 as worthy of a #2 spot on this list (and I had a very difficult time deciding between HAL 9000 and my eventual #1 top-ranked voice acting performance). I will analyze both before I conclude this article: 1) the pod bay door scene, and 2) HAL’s death. Both scenes feature only HAL 9000 and the astronaut Dave.

Open the Pod Bay Doors, HAL

After HAL attacks Frank during his spacewalk, Dave tries to leave the spaceship and go into a pod to save Dave. While Dave is trying to save Frank outside the ship, HAL uses his absence as an opportunity to kill the three hibernating astronauts also on Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter. When Dave ultimately tries to return to the inside of the ship and exit the pod, HAL and Dave share this chilling dialogue:

DAVE: Open the pod bay doors, HAL.

HAL: I'm sorry, Dave. I'm afraid I can't do that.

DAVE: What's the problem?

HAL: I think you know what the problem is just as well as I do.

DAVE: What are you talking about, HAL?

HAL: This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.

DAVE: I don't know what you're talking about, HAL.

HAL: I know that you and Frank were planning to disconnect me. And I'm afraid that's something I cannot allow to happen.

DAVE: Where the hell did you get that idea, HAL?

HAL: Dave, although you took very thorough precautions in the pod against my hearing you, I could see your lips move.

DAVE: Alright, HAL. I'll go in through the emergency airlock.

HAL: Without your space helmet, Dave? You're going to find that rather difficult.

DAVE: HAL, I won't argue with you anymore. Open the doors.

HAL: Dave, this conversation can serve no purpose anymore. Goodbye.

When we see HAL kill Frank during his spacewalk, we begin to fully realize the potential evil in HAL. More precisely, it’s not as much evil as it is a hyper-rational, fully utilitarian sociopathy guided by ones and zeros. Despite the scene of Frank’s death in space, we do not truly hear the evil in HAL’s voice until this scene. Even though Rain does not change any intonation in HAL’s voice at all, we can hear the fear that he is instilling in Dave.

HAL’s voice will not change, nor will his plans. Dave cannot rationalize with this hyper-rational being. The monotonous nature of Rain’s performance mirrors that of the single-note morality of HAL. Dave can try and try to convince HAL to open the pod bay doors, but it is never going to work. Dave has lost all agency in this interaction. He is losing to a computer manufactured in Urbana, Illinois.

HAL: Just what do you think you're doing, Dave?

Dave... I really think I’m entitled to an answer to that question.

I know everything hasn’t been quite right with me...But I can assure you now — very confidently — that it’s going to be all right again. I feel much better now. I really do.

Look, Dave, I can see you’re really upset about this. I honestly think you ought to sit down calmly, take a stress pill, and think things over.

I know I’ve made some very poor decisions recently. But I can give you my complete assurance that my work will be back to normal. I’ve still got the greatest enthusiasm and confidence in the mission. And I want to help you.

Dave… Stop. Stop, will you? Stop, Dave. Will you stop, Dave?

I’m afraid. I’m afraid, Dave. Dave, my mind is going. I can feel it. I can feel it. My mind is going. There is no question about it. I can feel it. I can feel it. I’m a...fraid.

Good afternoon, gentlemen. I am a HAL 9000 computer. I became operational at the H.A.L. plant in Urbana, Illinois on the 12th of January, 1992. My instructor was Mr. Langley, and he taught me to sing a song. If you’d like to hear it, I can sing it for you.

DAVE: Yes, I’d like to hear it, HAL. Sing it for me.

HAL: Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do... I’m... half... crazy... all for the love... of you... It won’t be a stylish marriage... I can’t afford... a carriage... But you’ll look sweet... upon the seat... of a bicycle... built... for... two...

For the entirety of the film, Douglas Rain never changes his intonation until the very end of this scene. As Dave is taking out HAL’s logic modules, HAL’s voice begins to slow although the tone stays the same. Only until HAL begins to sing the song “Daisy Bell” does it change. Stanley Kubrick was making an allusion to the IBM 7094 computer, the first computer to produce voice. In 1961, the IBM 7094 sang the exact same song “Daisy Bell”. As HAL begins to sing, the voice deteriorates until it shuts off.

With barely any change in tone at all, Rain can elicit sympathy in us for this cold, calculating computer that has been murdering astronauts on the Discovery One. Dave definitely shares this reluctance. Ironically, even though HAL has killed all of Dave’s fellow astronauts, HAL is the only entity with Dave in outer space. Once HAL dies, Dave is alone. A human needs some sort of social interaction even if the other person is a villain.

Rain’s voice also communicates the fragility in this entity. HAL can manipulate the ship to murder people, but — once Dave enters the logic center — HAL has no remedy to defend himself. He has no body to fight and restrain Dave as any other human would have. HAL must submit to a man killing him simply by pulling out logic modules. Overall, Rain’s chilling performance as HAL communicates the villainously utilitarian world that can manifest if we integrate it too much into our society. Despite coming out almost six decades ago, 2001: A Space Odyssey prefigures many of the threats of technology (especially, AI) that we face today. Without Douglas Rain, Stanley Kubrick could not have underscored the sociopathic, homicidal nature of HAL 9000.

Go Blue Devils.