Cleavages of Choice (and a Defense of Cats)

The newfound divisions in American politics in the Trump era

“Are you a racist? Do you hate Mexicans?” asks JD Vance in a television advertisement during his ultimately successful 2022 U.S. Senate campaign in Ohio.

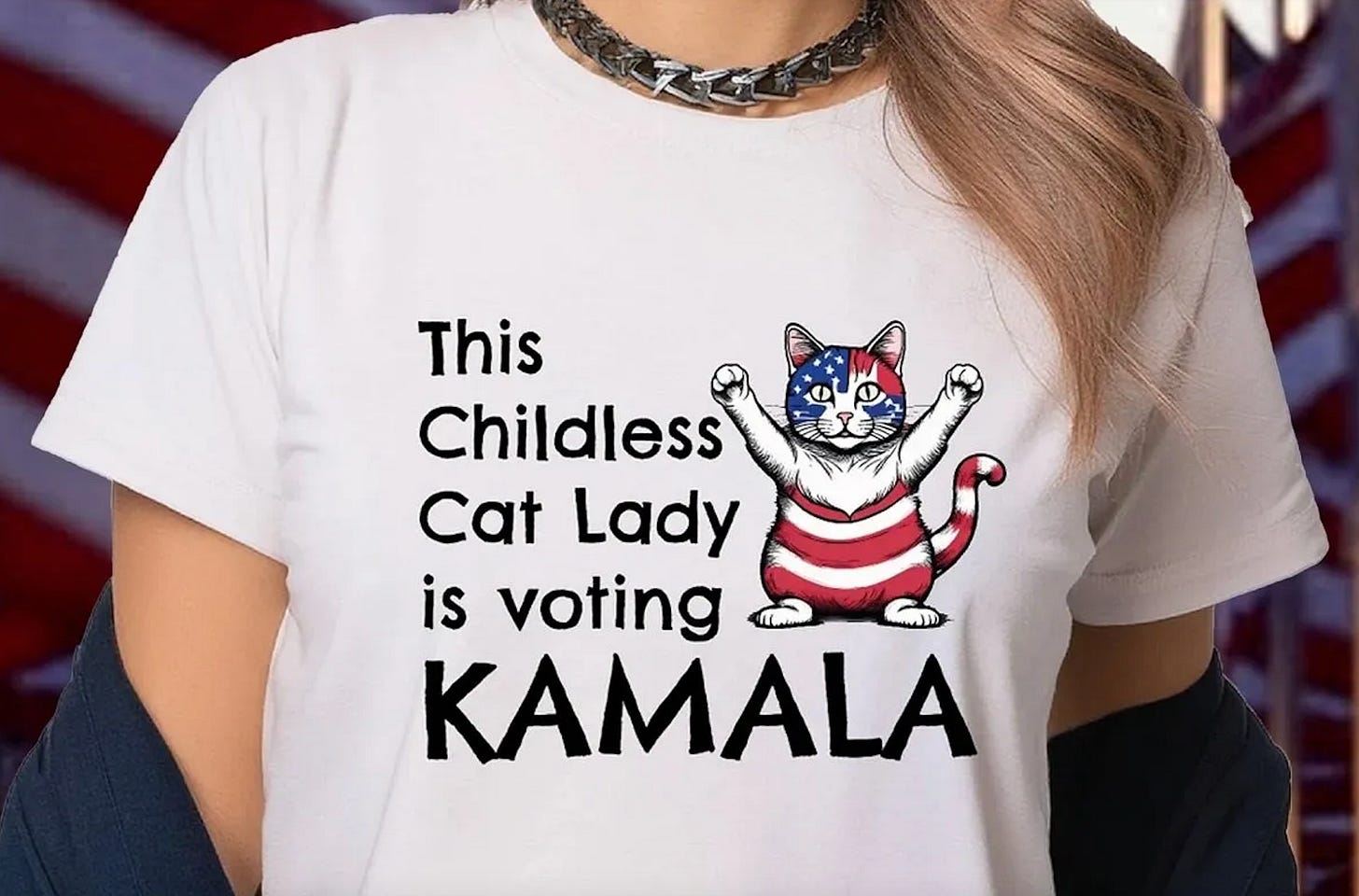

Two years later, Senator Vance has catapulted to perhaps being a heartbeat away for the presidency on January 20, 2025 — but, in the 2024 campaign, he seemingly has abandoned that tongue-in-cheek quip about perceived Republican bigotry toward Mexicans in favor of a different issue: the decision to have children. The Indigo Blob of the Democratic Party and the media has coalesced to attack Vance for his infamous comments about childless cat ladies.

Clearly, the 2024 election is becoming the most gendered election of our lifetimes, and we only recently got to this point not only because American voters suddenly have another chance to elect the first female president but also because Donald Trump chose JD Vance as his running mate, who has comments about childless cat ladies during hit on Tucker Carlson Tonight in July 2021. Beyond Harris’s sudden ascent to the top of the ticket and Trump’s selection of Vance, the June 2022 SCOTUS decision to overturn Roe vs. Wade obviously set the stage for this situation as did the fact that the G.O.P. has nominated Donald Trump for the third consecutive time. We do not need to recapitulate why the nomination of Trump adds a gendered dynamic to this campaign. We remember 2016.

Amid the increasing gender dynamics of the political landscape, Trump has also shown to be improving his numbers with non-white voters as compared to his performances in the prior two elections, and we have seen the different age cohorts becoming closer in their partisan leans. In polling, even after Harris’s entrance to the race, young people are supporting the Republican nominee at historic levels.

In other words, our cleavages in the American electorate are departing from our immutable characteristics. Although Democrats still dominate with Black voters and likely will still hold a majority with other ethnic groups, these immutable characteristics are no longer serving as strong of indicators of the candidate for whom a person will vote in November. Obviously, we cannot choose our race. We cannot choose our age, but — even if these characteristics have indicated presidential preferences in the past — they do not give as strong of a prediction as they used to give.

If Trump is closing the gap in these demographic groups, then why do we still have a very close election? Theoretically, Trump improving significantly with Hispanic and Black voters should guarantee his victory in November because the Democratic coalition has historically relied so heavily on Hispanic and Black votes. At least, the GOP autopsy after the 2012 loss against Barack Obama would have made that assertion. I doubt that any of the authors of that document would have expected that Donald Trump would have made those coveted gains with non-white voters that the autopsy craved.

The demographics of each party’s voter base changes from election to election, but — when your party gains with one specific electorate — you are likely losing somewhere else. Our duopolistic party system creates a game theory equilibrium in which neither party will ever win that much of a landslide because the parties tend to strategically adopt policy stances and rhetorical tactics to achieve a majority if they do not currently have one.

Therefore, where is Trump losing with voters? I will first note that, despite Harris’s rise in the polls, Trump is still performing better than he ever has been since he has started running for president in 2015 when you excise the strange, anomalous three weeks between the Trump-Biden debate on June 27 and Joe Biden’s sudden departure from the race on July 21.

While Trump is narrowing the gap in voting cohorts of immutable characteristics, such as ethnicity and age, he has simultaneously lost support in demographics defined by choices and not immutable characteristics. Consequently, defining choices are increasingly striking the political cleavages in our era instead of immutable traits. This shift began in the 2016 election, but it has continued ever since. Despite Trump’s victory in 2016, he did lose support among many groups since Mitt Romney’s loss against Barack Obama in 2012. The media has beaten this narrative to death by now, but Trump has obviously led to Republican losses with college-educated voters and suburbanites.

A Cleavage of Choice

What is a cleavage of choice? Firstly, a political cleavage is anything that politically splits one group from another. I already gave the examples of ethnicity and age. With those descriptors, we can strike many different cleavages in the population. The male vs. female divide probably creates the most stark cleavage because it is roughly 50-50.

I already gave the most salient example of a cleavage of choice: college education. People do not choose their race or their age, but they can choose to go to college or receive even higher education. When we look at election results or pre-election polling, we can usually see even more cleavages of choice beyond level of education:

college education

marital status

union membership

military service

area of residence (urban, suburban, or rural)

frequency of religious service attendance

having children

All of the above seven factors demonstrate what I am calling cleavages of choice. We have already discussed marital status and the number of children that one has in the article in the context of Vance’s comments on “childless cat ladies”. Demographics traits, such as these, are more and more defining our politics today as opposed to the immutable characteristics of ethnicity and age.

How It Used to Be

In the mid-20th century, we had a pretty defined idea of which groups voted for which party. African Americans voted Democrat. College graduates voted Republican. Catholics — dominated by Italian and Irish immigrants — voted Democrat. Mainline Protestants voted Republican. Cuban immigrants voted Republican. Working class people — especially, union members — voted Democrat. Old people voted Republican. Young people voted Democrat. Men voted Republican. White Southerners voted Democrat.

Obviously, I am giving you broad-brush generalizations, but our understanding of political cleavages at that period of American history conformed to those axioms. The South would never vote Democrat until Republicans, such as Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, started flipping it.

For the most part, you will notice that most of those cleavages come from immutable characteristics. One could argue that one chooses their religion. To an extent, that is true, but — in that era — people inherited their religion by virtue of how their parents raised them. You cannot choose what religion your parents follow if they follow one at all. In other words — if your parents or grandparents immigrated from Italy or Ireland — you likely grew up in the Catholic Church, a family tradition that you inculcated in your own children.

How It Is Today

Now, those cleavages of choice are largely predicting one’s voting habits. Regardless of the type of cleavage, campaigns will always try to appeal to certain specific demographics. For decades, Democrats have won elections by relying on a high turnout from the Black electorate, so the party has historically used messaging aimed at appealing to African Americans.

Partisan lean by a cleavage of choice has a different psychological impact on a voter. In the past, you did not think much of your vote as you often voted out of habit because of your demographic traits. Your parents passed their partisanship down to you. Black people vote Democrat. Jews vote Democrat. Evangelical Christians vote Republican. Cubans vote Republican. It’s just second nature.

You harbor more insecurity about a choice-defining trait than an immutable trait. If you are African American, you may have anguish because of perceived injustice toward your demographic group in the United States, but you are likely not insecure about being African American in the same way. In fact, you probably have pride in your heritage, and most groups do. You never have to question whether it was a good choice to become African American. Why? Well, you do not decide to become African American. You are born into it. This applies to any immutable demographic trait.

On the other hand, in this new era, you may very well harbor insecurity about your choice. We can take the trait of “college-educated”. You enter that group because of a perceived choice to go to college. If someone criticizes you for college education or marginalizes the out-of-touch attitudes of the college-educated voters, then you might start questioning your own decision. You need to justify what you did. It was worth it to take out those loans. It was worth it to go to medical school. It was worth it to go to residency. It was worth it to delay starting a family. You do not need to make the same sort of rationalizations about being African American because you cannot change that fact about yourself.

Consequently, if somebody attacks the college-educated elites, you take it personally because, for a moment, you might question if you made the correct decisions — so you enter the litany of rationalizations that I just gave. Furthermore, even if you are a member of an underrepresented group defined by an immutable characteristic, you have a group of people with whom you can find pride. As for the cleavages based on personal decision, well … that’s personal. You may have gone to college with thousands of people, but each of your decision was a personal “journey”.

Vance’s Comments

In Vance’s controversial comments on Tucker Carlson Tonight in 2021, he hit multiple cleavages of choice, and one of these divisions might have the most personal attack on someone: the decision to not have children. Vance’s full quote stated:

“We are effectively run in this country, via the Democrats, via our corporate oligarchs, by a bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives and the choices that they've made, and so they want to make the rest of the country miserable, too.

“And it’s just a basic fact if you look at Kamala Harris, Pete [Buttigieg], AOC — the entire future of the Democrats is controlled by people without children. And how does it make any sense that we’ve turned our country over to people who don’t really have a direct stake in it.”

Let’s dissect the term “childless cat lady”, which includes three characteristics about a person:

having no children

owning a cat

being a woman

To begin, being a woman is an immutable characteristic. Speaking about women themselves actually does not create as much division as one may assume. When a group comprise half of the population, it then becomes much more heterogeneous. In other words, it is very hard for the entire female population or the entire male population to agree on a common political issue. In fact, in 2020, women comprised slightly over a majority of voters at 52 percent. In 2016 and 2020, Trump lost women by the same margin of 13 percentage points, which some people may see as a strong margin, but that margin is nowhere near as big as the margins in other demographic groups. Nonetheless, I will get to the issue of “womanhood” and voting later on.

The Politics of Childlessness

Perhaps the “ladies” part of Vance’s comment drew the most attention, but I do not think that it drew the most ire. Instead, I believe that the “childless” part elicited the most internal anguish even if people claim that he attacked women. Why do I make this assertion? Again, you cannot choose to be a woman, and the female electorate has much more ideological diversity and heterogeneity than Democrats would want you to think.

Conversely, being “childless” goes to one of those cleavages of choice, and it hits someone personally more than the attainment of higher education (or lack thereof). We must acknowledge the decision to have children as an intensely personal one. The number of children that people have can signal so many other broader choices that a woman has made in her life.

If you have a large number of kids, you might be highly religious. Perhaps you follow Catholicism and do not use birth control, so you naturally will have more children with your husband than otherwise. A high number of children also indicates that you must have started having children at a younger age, which often correlates with a younger age at marriage.

You must start having children at a young age to ultimately have many children. If you look at the chart above, a woman has pretty stable fertility from age 20 to age 32, but then fertility precipitously drops between age 32 and age 42. Later into her forties, a woman will enter menopause at some point, and — even if she has not entered menopause — the ability for pregnancy becomes inordinately difficult.

This point of mine may prompt some people to respond that it is possible for a woman to have a baby in her mid-forties nowadays. This is correct, but who has this opportunity? We now have many modern fertility treatments that allow older women to have babies: in vitro fertilization, fertility drugs, freezing eggs, etc. This fact strikes another relevant cleavage — the inequity of wealth.

The deceptive tabloids:

We can read tabloid articles about female celebrities who had their first children well into their forties: Madonna, Nicole Kidman, Halle Berry, etc. Let me ask you a question. What similarity does an average college-educated woman making a six-figure salary at a law firm have with Madonna? Besides having a uterus, there isn’t much.

With very little financial issue, Madonna and those other female celebrities can afford to pursue all those costly fertility treatments. According to Forbes, IVF can cost up to $30 thousand nowadays, and IVF is difficult. You do not just pay $30 thousand and have a baby pop out. Can that 42-year-old attorney afford to pay that much? Maybe she has the willingness to do so, but I bet that she does so with hesitation. A price tag of $30 thousand burdens families even in the top one percent of income-earners.

The anecdotes of celebrities having late births manipulate and mislead average women who might be choosing to delay starting a family. The above image shows the cover of an issue of People magazine from October 28, 1996. It features Madonna, who — at age 42 at the time — had just given birth to her first baby.

With this cover and this headline, People is trying to increase Madonna’s relatability to the target audience of female readers interested in celebrity news and gossip. It displays an intimate image of the father Carlos Leon and Madonna in embrace and, likely, in the middle of a kiss. How lovely! They’re just like you and your husband!

The magazine presents Madonna’s motherhood story as a normal one, but it is not. It manipulates vulnerable readers who see Madonna having a baby at age 42 and assuming that, if she can do it, I can do it too. Firstly, perhaps you can’t do it, and — secondly — if you can do it — then you likely need those expensive fertility treatments only affordable to wealthy people, such as Madonna and Halle Berry. This is a story — not the norm. If it were the norm, then People wouldn’t so frequently showcase these anecdotes.

Now, let’s analyze the situation of having no children (or perhaps only one or two). The fertility rate is dropping in the West because of many factors, largely, increased access to effective birth control and increased freedom for women to enter the workforce. The latter also includes the fact that more and more women are attaining higher education and doing so now at a higher rate than American men.

Pursuing higher education and, then, a career often stifles a woman’s ability to have many children (if any at all). In the wake of the third-wave feminism movement of the 1980s and 1990s, many Boomer and Gen X women implied that children can burden your career — and, yes, they can. Even if you wanted kids, you could always resort to the expensive fertility treatments.

The opening scene of Mike Judge’s 2006 film Idiocracy lampoons the idea of the college-educated, wealthy family postponing having children.

The scene juxtaposes the highly educated couple struggling to have children while the stereotypically redneck family endlessly reproduces and has the bloodline extend for five centuries. Meanwhile, the highly educated woman ultimately has no children, and the bloodline of her and her husband dies.

Kat Rosenfield of The Free Press touched on these ideas in her essay “What the Childless Among Us Leave Behind” from August 7, 2024. She also speaks on it on Ethan Strauss’s Substack podcast House of Strauss, which he has behind the Substack paywall. Rosenfield is responding to Vance’s comments. She herself never had children and, yes, owns a cat — but she does not deride Vance. She believes that the older generation of Boomer and Gen X feminists sold a false bill of goods to the millennials.

The Boomer parents of the 1980s and 1990s claimed that their children could achieve anything. The Boomers came out of an era of post-WWII abundance and never had the struggles that the Greatest Generation and the Silent Generation had during the Great Depression and World War II. Out of all generations in American history, the Boomers were truly born on third base but thought they had hit a triple.

Part of the mantra of “achieve anything” includes the assertion that women can wait to have children to advance their careers, which obviously went against the norms of the 1950s and 1960s before the Sexual Revolution and the 1973 Supreme Court case Roe vs. Wade. Consequently, the children of the Boomers — the millennials — have suffered the most from this fantasy. Now, the millennials have had the least children out of all the generations. Many zoomers are even seemingly bucking that trend and embracing social conservatism again through the embrace of the Catholic Church on the Internet and “trad wife” culture, which deserves its own article altogether.

This Boomer notion of invincibility and endless opportunity peak in the late 2000s and early 2010s. I usually associate it with Sheryl Sandberg at Facebook, where she served as COO from 2008 to 2022. Her 2013 book Lean In gave a blueprint for women who wanted not only to have successful careers but also to raise a family. This culture shift was assumedly culminating in the 2016 election of Hillary Clinton, the first female president, but Clinton obviously lost in a shock upset against Trump. Her loss killed the Sandberg era of “girl boss feminism”, but Kamala Harris might be trying to resuscitate it. Maybe Harris will successfully do so if she defeats Trump, the man who last stopped a woman from entering the White House.

Author Ginevra Davis writes about this concept in her essay “How Feminism Ends”, published in the Spring 2024 issue of American Affairs:

The 2010s were supposed to be the end of feminism—in that the project would reach its perfect, inevitable conclusion. Girls were supporting girls. Taylor Swift had a squad. Hillary Clinton was about to become the forty-fifth president of the United States. But toward the end of the decade, something snapped. The project hit a snag. By 2021, cool girls online were bragging about becoming “tradwives” and staying at home with their boyfriends. Part of feminism’s branding problem was that, when allowed to compete fairly, women were not measuring up in a few key professional fields—which led to broad-scale affirmative action on the basis of gender, to preserve the illusion, for men and women alike, that history was still lumbering along as planned.

Harris is clearly trying to revive the pre-Trump 2010s in her campaign. Will it work? There is approximately a 50% chance, but she is weaponizing Vance’s attack on women’s personal choices.

How do the cats come into play? The final “choice” that Vance included in his comment was about owning cats. Obviously, one must decide to own a cat, but how can we be politicizing the most common pet in the United States? Plenty of men own cats too. Plenty of Trump voters own cats. Well, the cats become a metaphor. Plenty of families with children own cats as pets, but — if a childless, unmarried woman owns a cat — it elicits certain connotations and stereotypes. It probably shouldn’t, but it does.

That 2020 cover of The New Yorker

I distinctly remember the above cover of The New Yorker from December 7, 2020 — as that horrid year was drawing to a close. Cartoonist Adrian Tomine produced that cover. He frequently produces cartoons for The New Yorker, historically known for its provocative and satirical covers — a purportedly high-brow version of what the New York Post does.

This cartoon perfectly encapsulated the day-to-day life of many Americans at that point in the pandemic, and The New Yorker provided the perfect venue to display such a cartoon. The covers of The New Yorker often communicate what the observations of the coastal elites are thinking at the cultural moment. They serve as an integral institution in the Village or the Indigo Blob, metaphors that Nate Silver uses in his new book On the Edge.

The Village just includes every component of the establishment consensus: academia, media, the Democratic party, government, etc. The Village is concentrated on East Coast coastal cities — particularly, New York with media and finance, Washington with the government, and Boston with the academia. The Indigo Blob describes that group of Villagers in a political way. Silver uses the color indigo because it is a mix of Democratic blue and centrist purple, yet it still is much closer to blue than Republican red.

If The New York Times transmits stories on current events and editorials to the members of the Indigo Blob, then The New Yorker (along with New York Magazine and The Atlantic) provides the incisive, snarky essays and satire that go beyond the length of a normal newspaper article, so what is this cartoon saying? It hits so much of the imagery that Vance evoked in his infamous comments.

Out of the gate, we know that many places of business were still only meeting virtually in December 2020. Everyone was working from home. Okay … well, everyone who readers of The New Yorker knew. Why do I make this point? Only certain portions of the workforce could stay home. The knowledge workers — almost all college-educated — could stay at home and relax in their pajamas while they hopped on Zoom periodically throughout the day. On the other side of the tracks, nobody with a manual, blue-collar class job could stay at home. You can’t fix the plumbing of a toilet from Zoom, and you definitely cannot deliver Uber eats to the subject of this cartoon from Zoom. This is not Willy Wonka’s factory. We cannot not transmit food through a television screen yet.

Already, this cartoon depicts a reality only experienced by college-educated and, likely, wealthier Americans. If you work in such an industry, then you likely do not know many people in blue-collar work. I am not deriding college-educated workers for this reality. I live in a college-educated bubble too, but it harkens back to the thesis of Charles Murray’s 2012 book Coming Apart, which chronicled the ever-growing chasm between working class white Americans and the college-educated elites. You can even take Murray’s “Do you live in a bubble quiz” here. In the least sympathetic light, we essentially live in two different realities now.

However, let’s return to the contents of the cartoon in itself. What objects are surrounding the woman? She is drinking some sort of cocktail in a martini glass as she attends a Zoom meeting on her laptop. Beneath her desk, she is scrolling on her phone, indicating her detachment from whatever is happening on Zoom. She wears a professional blouse appropriate for the in-person workplace, yet she wears athletic shorts on the bottom half of her torso. On her feet, she wears some sort of fluffy slippers. Trash inundates her floor, desks, and tabletops — so she obviously has not been cleaning the house while she has been working remotely.

For one, the lockdown has likely vastly increased her laziness so that she will not want to clean up. An empty bag of Cheetos sits there and communicates to us that this woman is not eating ideally during this time. She has two cardboard Amazon boxes beneath her desk. She has opened one but not the other. The boxes further mark her separation with society. She cannot leave her house to shop anymore. Instead, she works from home to stay safe from COVID-19 while a blue-collar wage worker is delivering her Amazon boxes up the steep flights of stairs in her apartment complex.

Along with her cocktail, we can see three wine bottles atop her refrigerator, so she is clearly drinking regularly throughout the day. She is drinking while she is meeting on Zoom for gosh sake! Tomine presents this alcohol use in a relatable and humorous manner, but we all know that the pandemic increased alcoholism and alcohol use throughout day. During the lockdowns, the days blurred. It did not matter if it was morning or night. In that case, why wouldn’t this woman drink during work?

On the floor, you will notice artifacts from the pandemic era: two masks, two bottles of hand sanitizer, and rubber gloves. These physical objects remind us that this woman must put on a layer of armor to go outside as if she is entering battle, yet — inside — she can take off the armor. She can escape the suffocation. These items all just serve as physical reminders of the fragility that many people experienced. If this woman reads The New Yorker and has a virtual job, then she is likely 1) living in a city with strict COVID-19 protocols and 2) personally anxious about others not taking the vaccine. Perhaps, more specifically, she is more personally anxious about her liberal cohorts think that she is not “with the program”. Only Trump supporters do not wear masks. I conjecture that she might live in New York City because, on the floor, she has a tote bag with the “I Love New York” icon on it.

However, for the political discourse of the past few weeks, the cats in the cartoon have the most salience. What relevance do her two cats have? They really complete the entire depiction of this post-pandemic archetypal female white-collar professional, the exact sort of woman that Vance was sarcastically deriding. Why do people try to politicize cats? We do have the pop culture trope of the single woman with a cat, but — for social conservatives like Vance — the cats carry much more symbolic weight.

When Vance connects the words “childless” and “cat”, he is implying that the cats in these women’s lives are filling the void that biological human children would otherwise fill. In this cartoon and in Vance’s characterization, a specter of loneliness haunts these liberal-coded women, but couldn’t any species of pet fill this void? Why do Vance and other conservatives not attack dogs? If a woman was filling the childless void with a pet, couldn’t she also do so with a dog? In a way, a dog might even further fill the void of a child. A dog needs way more constant attention than a cat does. We need to treat dogs somewhat as babies while we can leave cats to their own devices. We do not need to walk them. They urinate and defecate in a litter box, and they do not constantly want our attention.

I think that cats just have a female-coded energy even though 50% of cats are necessarily male. Perhaps cats’ relatively smaller size to the average dog plays a role even though plenty of toy dogs weigh less than many cats. Dogs do have a more rambunctious and aggressive energy. Regardless, perhaps we are unfairly vilifying the cat, a species that we chose to domesticate. Cats had no say in all of this, but the cat still demonstrates a cleavage of choice.

The woman in the cartoon and the women whom Vance attacked chose to have a cat, and Vance is ascribing some sort of meaning that a cat does not necessarily have. Perhaps people just like cats as they like dogs, but the cats become the butt of a joke in an attempt by Vance to use humor to appeal to lowest-common-denominator shock jock commentary on Tucker Carlson Tonight. I agree with Vance on the issue of childlessness and anti-natalism in the United States, but his comment bothered me more so because it showed that he was making an attempt to deliver a funny line, one that we know that he forced inorganically.

Final thoughts: I do not envision a political landscape anytime soon when each side stops personally attacking the other one. We can go back to Clinton’s “deplorables” comment in 2016. Everyone does it, but — at a more macroscopic level — immutable characteristics are waning in political salience. This is good, but it is coming at the cost of politicizing somebody’s deeply personal choices in life.

You had me at "And a Defense of Cats" in the title, haha. Great piece as always, Craig! And here's hoping, perhaps a bit too optimistically, that identity politics (both around immutable traits AND choices) fades out just in time for the 2028 election.